STRATEGIES

Move technology to invisibility.

As technology becomes ubiquitous it also becomes invisible. The more chips proliferate, the less we will notice them. The more networking succeeds, the less we'll be aware of it.

In the early 1900s, at the heroic stage of the industrial economy, motors were changing the world. Big, heavy motors ran factories and trains and the gears of automation. If big motors changed work, they were sure to change the home, too. So the 1918 edition of the Sears, Roebuck catalog featured the Home Motor--a five-pound electrical beast that would "lighten the burden of the home." This single Home Motor would supply all the power needs of a modern family. Also for sale were plug-ins that attached to the central Home Motor: an egg beater device, a fan, a mixer, a grinder, a buffer. Any job that needed doing, the handy Home Motor could do. Marc Weiser, a scientist at Xerox, points out that the electric motor succeeded so well that it became invisible. Eighty years later nobody owns a Home Motor. We have instead dozens of micro-motors everywhere. They are so small, so embedded, and so common that we are unconscious of their presence. We would have a hard time just listing all the motors whirring in our homes today (fans, clocks, water pumps, video players, watches, etc.). We know the industrial revolution succeeded because we can no longer see its soldiers, the motors.

Computer technology is undergoing the same disappearance. If the information revolution succeeds, the standalone desktop computer will eventually vanish. Its chips, its lines of connection, even its visual interfaces will submerge into our environment until we are no longer conscious of their presence (except when they fail). As the network age matures, we'll know that chips and glass fibers have succeeded only when we forget them. Since the measure of a technology's success is how invisible it becomes, the best long-term strategy is to develop products and services that can be ignored.

If it is not animated, animate it.

Just as the technology of writing now covers almost everything we make (not just paper), so too the technologies of interaction will soon cover all that we make (not just computers). No artifact will escape the jelly bean chip; everything can be animated. Yet even before chips reach the penny price, objects can be integrated into a system as if they are animated. Imagine you had a million disposable chips. What would you do with them? It's a good bet that half of the value of those chips could be captured now, with existing technology, by creating a distributed swarmlike intelligence using such dumb power.

If it is not connected, connect it.

As a first step, every employee of an institution should have intimate, easy, continuous access to the institution's medium of choice--email, voicemail, radio, whatever. The benefits of communication often don't kick in until ubiquity is approached; aim for ubiquity. Every step that promotes cheap, rampant, and universal connection is a step in the right direction.

Distribute knowledge.

Use the minimal amount of data to keep all parts of a system aware of one another. If you operate a parts warehouse, for example, your system needs to be knowledgeable of each part's location every minute. That's done by barcoding everything. But it needs to go further. Those parts need to be aware of what the system knows. The location of parts in a warehouse should shift depending on how well they sell, what kind of backlog a vendor forecasts, how their substitutes are selling. The fastest-moving items (which will be a dynamic list) may want to be positioned for easier picking and shipping. The items move in response to the outside--if there is a system to spread the info.

Get machines to talk to one another directly. Information should flow laterally and not just into a center, but out and between as well. The question to ask is, "How much do our products/services know about our business?" How much current knowledge flows back into the edges? How well do we inform the perimeter, because the perimeter is the center of action.

If you are not in real time, you're dead.

Swarms need real-time communication. Living systems don't have the luxury of waiting overnight to process an incoming signal. If they had to sleep on it, they could die in their sleep. With few exceptions, nature reacts in real time. With few exceptions, business must increasingly react in real time. High transaction costs once prohibited the instantaneous completion of thousands of tiny transactions; they were piled up instead and processed in cost-effective batches. But no longer. Why should a phone company get paid only once a month when you use the phone every day? Instead it will eventually bill for every call as the call happens, in real time. The flow of crackers off grocery shelves will be known by the cracker factory in real time. The weather in California will be instantly felt in the assembly lines of Ohio. Of course, not all information should flow everywhere; only the meaningful should be transmitted. But in the network economy only signals in real time (or close to it) are truly meaningful. Examine the speed of knowledge in your system. How can it be brought closer to real time? If this requires the cooperation of subcontractors, distant partners, and far-flung customers, so much the better.

Count on more being different.

A handful of sand grains will never form an avalanche no matter how hard one tries to do it. Indeed one could study a single grain of sand for a hundred years and never conclude that sand can avalanche. To form avalanches you need millions of grains. In systems, more is different. A network with a million nodes acts significantly different from one with hundreds. The two networks are like separate species--a whale and an ant, or perhaps more accurately, a hive and an ant. Twenty million steel hammers swinging in unison is still 20 million steel hammers. But 20 million computers in a swarm is much, much more than 20 million individual computers.

Do what you can to make "more." In a network the chicken-and-egg problem can hinder growth at first--there's no audience because there is no content, and there is no content because there is no audience. Thus, the first efforts at connecting everything to everything sometimes yield thin fruit. At first, smart cards look no different from credit cards--just more inconvenient. But more is different; 20 million smart cards is a vastly different beast than 20 million credit cards.

It's the small things that change the most in value as they become "more." A tiny capsule that beeps and displays a number, multiplied by millions: the pager system. What if all the Gameboys or Playstations in the world could talk to one another? What if all the residential electric meters in a city were connected together into a large swarm? If all the outdoor thermometers were connected, we would have a picture of our climate a thousand times better than we have ever had before.

The ants have shown us that there is almost nothing so small in the world that it can't be made larger by embedding a bit of interaction in many copies of it, and then connecting them all together.

The game in the network economy will be to find the overlooked small and figure out the best way to have them embrace the swarm.

Create feedback loops.

Networks sprout connections and connections sprout feedback loops. There are two elementary kinds of loops: Self-negating loops such as thermostats and toilet bowl valves, which create feedback loops that regulate themselves, and self-reinforcing loops, which are loops that foster runaway growth such as increasing returns and network effects. Thousands of complicated loops are possible using combinations of these two forces. When internet providers first started up, most charged users steeper fees to log on via high-speed modem; the providers feared speedier modems would mean fewer hours of billable online time. The higher fees formed a feedback loop that subsidized the provider's purchase of better modems, but discouraged users from buying them. But one provider charged less for high speed. This maverick created a loop that rewarded users to buy high-speed modems; they got more per hour and so stayed longer. Although it initially had to sink much more capital into its own modem purchases, the maverick created a huge network of high-speed freaks who not only bought their own deluxe modems but had few alternative places to go at high speed. The maverick provider prospered. As a new economy business concept, understanding feedback is as important as return-on-investment.

Protect long incubations.

Because the network economy favors the nimble and quick, anything requiring patience and slowness is handicapped. Yet many projects, companies, and technologies grow best gradually, slowly accumulating complexity and richness. During their gestation period they will not be able to compete with the early birds, and later, because of the law of increasing returns, they may find it difficult to compete as well. Latecomers have to follow Drucker's Rule--they must be ten times better than what they hope to displace. Delayed participation often makes sense when the new offering can increase the ways to participate. A late entry into the digital camera field, for instance, which offered compatibility with cable TV as well as PCs, could make the wait worthwhile.

It's a hits game for everyone.

In the network economy the winner-take-all behavior of Hollywood hit movies will become the norm for most products--even bulky manufactured items. Oil wells are financed this way now; a few big gushers pay for the many dry wells. You try a whole bunch of ideas with no foreknowledge of which ones will work. Your only certainty is that each idea will either soar or flop, with little in between. A few high-scoring hits have to pay for all the many flops. This lotterylike economic model is an anathema to industrialists, but that's how network economies work. There is much to learn from long-term survivors in existing hits-oriented business (such as music and books). They know you need to keep trying lots of things and that you don't try to predict the hits, because you can't.

Two economists proved that hits--at least in show biz--were unpredictable. They plotted sales of first-run movies between May 1985 and January 1986 and discovered that "the only reliable predictor of a film's box office was its performance the previous week. Nothing else seemed to matter--not the genre of the film, not its cast, not its budget." The higher it was last week, the more likely it will be high this week--an increasing returns loop fed by word of mouth recommendations. The economists, Art De Vany and David Walls, claim these results mirror a heavy duty physics equation known as the Bose-Einstein distribution. The fact that the only variable that influenced the result was the result from the week before, means, they say, that "the film industry is a complex adaptive system poised between order and chaos." In other words, it follows the logic of the net: increasing returns and persistent disequilibrium.

Check for externalities.

The initial stages of exponential growth looks as flat as any new growth. How can you detect significance before momentum? By determining whether embryonic growth is due to network effects rather than to the firm's direct efforts. Do increasing returns, open systems, n2 members, multiple gateways to multiple networks play a part? Products or companies or technologies that get slightly ahead--even when they are second best--by exploiting the net's effects are prime candidates for exponential growth.

Coordinate smaller webs.

The fastest way to amp up the worth of your own network is to bring smaller networks together with it so they can act as one larger network and gain the total n2 value. The internet won this way. It was the network of networks, the stuff in between that glued highly diverse existing networks together. Can you take the auto parts supply network and coordinate it with the insurance adjusters network plus the garage repair network? Can you coordinate the intersection of hospital records with standard search engine technology? Do the networks of county property deed databases, U.S. patents, and small-town lawyers have anything useful in common? Three thousand members in one network are far more powerful than one thousand members in three networks.

Touch as many nets as you can.

Because the value of an action in the network economy multiplies exponentially by the number of networks that action flows through, you want to touch as many other networks as you can reach. This is plentitude. You want to maximize the number of relations flowing to and from you, or your service or product. Imagine your creation as being born inert, like a door nail off a factory conveyor belt. The job in the network economy is to link the nail to as many other systems as possible. You want to adapt it to the contractor system by making it a standard contractor size so that it fits into standard air-powered hammers. You want to give it a SKU designation so it can be handled by the retail sales network. It may want a bar code so it can be read by a laser-read checkout system. Eventually, you want it to incorporate a little bit of interacting silicon, so it can warn the door of breakage, and take part in the smart house network. For every additional system the nail is a part of, it gains in value. Best of all, the systems and all their members also gain in value from every nail that joins.

And that's just for a stick of iron. More complex objects and services are capable of permeating far more systems and networks, thus greatly boosting their own value and the plentiful value of all the systems they touch.

Maximize the opportunities of others.

In every aspect of your business (and personal life) try to allow others to build their success around your own success. If you run a hotel, what can you do to permit others--airlines, luggage retailers, tour guides--to be part of your network? Rather than viewing their dependency on your success as a form of parasitism, or worse, as a rip-off, understand this tight coupling as sustenance. You want to entice others to create services centered around the customer attention you have won, or to supply add-ons to your product, or even, if it is a new-fangled idea, to create legal imitations. This is a counter-intuitive stance at first, but it plays right into the logic of the net. A small piece of an expanding pie is the biggest piece of all. Software is especially primed to work this way. The programmers who created the hit game Doom deliberately made it easy to modify. The results: Hundreds of other gamers issued versions of Doom that were vastly better than the original, but that ran on the Doom system. Doom boomed and so did some of the derivatives. The software economy is full of such examples. Third-party templates for spreadsheets, word processors, and browsers make profits for both the third-party vendor and the host system. It takes only a bit of imagination to see how the leveraging of opportunities also works in domains outside of software. When confronted with a fork in the road, if all things are equal, go down the path that makes the opportunities of others plentiful.

Don't pamper commodities...

...let them flow. The cost of replicating anything will continue to go down. As it does, the primary cost will be developing the first copy, and then getting attention to it. No longer will it be necessary to coddle most products. Instead they should be liberated to flow everywhere. Let's take pharmaceuticals, especially genetically bio-engineered pharmaceuticals. The cost of little pills in the drug store can be hundreds of times greater than what they cost to produce in quantity, yet many drugs are priced expensively in order to recoup their astronomical development costs. Pharmaceutical companies treat and price their drugs as scarcities. One can expect, however, that in the future, as drug design becomes more networked, more data-driven, more computer mediated, and as drugs themselves become smarter, more adaptive, more animated, the competitive advantage will go to those companies that let "copies" of the drug flow in plentitude. For example, a highly evolved bioengineered headache relief drug may be sold for a few dollars on a "take as much as you need" basis. The company makes its profits when you pay it handsomely for tailoring that drug specifically for your DNA and your body. Once designed, you pay almost nothing for additional refills. Indeed there are already a few start-up biotech companies headed this way. The field is called parmacogenomics. They are heeding the call of plentitude.

Avoid proprietary systems.

Sooner or later closed systems have to open up, or die. If an online service requires dialing a special phone number to reach it, it's moribund. If it needs a special gizmo to read it, it's kaput. If it can't share what it knows with competing goods, it's a loser. Closed systems close off opportunities for others, making leverage points scarce. This is why the network economy--which is biased toward plenty--routes around closed systems. One could safely bet that America Online, WebTV, and Microsoft Network (MSN)--three somewhat closed systems--will eventually go entirely onto the open web, or disappear. The key issue in closed-versus-open isn't private versus public, or who owns a system; often private ownership can encourage innovation. The issue is whether it is easy or difficult for others to invent something that plays off your invention. The strategic question is simple: How easy is it for someone outside of the host company to contribute an advance to their system or product or service? Are the opportunities for participating in your own network scarce or plentiful?

Don't seek refuge in scarcity.

Every era is marked by the wealth of those who figure out what the new scarcity is. There will certainly be scarcities in the network economy. But far greater wealth will be made by exploiting the plentitude. To make sure you are not seeking refuge in scarcity, ask yourself this question: Will your creation thrive if it becomes ubiquitous? If its value depends on only a few using it, you should reconsider it in light of the new rules.

What can you give away?

This is the most powerful question in this book. You can approach this question in two ways: What is the closest you can come to making something free, without actually pricing it at zero? Or, in a true gesture of enlightened generosity, you can figure out how to part with something very valuable for no monetary return at all. If either strategy is pursued with intelligence, the result will be the same. The network will magnify the value of the gift. But giving something away is not usually easy. It must be the right gift, given in the proper context. To figure out what to give away, consider these questions:

- Is the freebie more than a silly premium, like the toy in a cereal box? There is no power in the gift unless it is crucial to your business.

- What virtuous circle will this freebie circulate in? Is it the loop you most need to amplify?

- In the long run, the unbounded support of a customer is more valuable than a fixed amount of their money. How will you eventually capture the support of customers if there is initially no flow of money?

Every organization harbors at least one creation--or potential creation--that can be liberated into "freedom." This is often an idea with problems, particularly with its price: Should it be $69.50 per minute or $6.50 per box? The answer sometimes is: It should be free. Even if the idea is never actualized, my experience is that the very act of contemplating the free will inevitably illuminate all kinds of beneficial attributes that were never visible before. "Free" has long been a taboo price point. Perhaps because it has been forbidden, many low-hanging fruit are waiting to be plucked by giving the free serious consideration.

Act as if your product or service is free.

Magazine publishers do this. The cover price on a magazine barely covers the cost of printing it, so publishers act as if they were giving it away (and some actually do). They make their money instead on advertising. Says pundit Esther Dyson, "The creator who immediately writes off the costs of developing content--as if it were valueless--is always going to win over the creator who can't figure out how to cover those costs." Memberships in serious discounters such as Cendant are also "as if free." Cendant "gives away" the merchandise very near the cost of manufacturing, as if the stuff were free. They make the bulk of their profits not from selling goods to its members--who get fantastic retail prices--but from selling $40 per year membership fees.

Invest in the first copy.

That is the only one that will hurt. The second copy and all thereafter will head toward the free, but the first will become increasingly more expensive and capital intensive. Gordon Moore, of Moore's Law fame, posed a second law: that the costs of inventing chips (that are halving in cost every 18 months) is doubling every three to four years. The up-front investment for research, design, and process invention for all complex endeavors are commanding a larger share of the budget, while the capital costs of subsequent copies diminishes.

Anticipate the cheap.

What would you do if your current offerings cost only one third what they cost today? They will someday soon, so create models that recognize this trend.

Turn off the meter, charge for joining.

Flat or monthly fixed pricing is one way of pricing "as if free." Fees are paid, but there is no meter running. This tactic can be abused by the company (a la cable TV) or can be abused by the consumer (a la AOL). A flat fee is one type of subscription. Subscriptions are well-honed tools used by the soft world of magazines and theater, among others. Could subscriptions really apply to old order physical products, like say, food? The idea of subscribing to food is not so outlandish. Forty years ago subscriptions to milk were quite common. There were also subscriptions to bread and beer and other staples. Subscriptions tend to emphasize and charge for intangible values: regularity, reliability, first to be served, and authenticity, and work well in the arena of "as if free."

The ancillary market is the market.

The software is free, but the manual is $10,000. That's no joke. Cygnus Solutions, based in Sunnyvale, California, rakes in $20 million per year in revenues selling support for free Unix-like software. Apache is free but you can buy support and upgrades from C2Net. Although Novell, the network provider, does sell network software, that's not what they are really selling, says Esther Dyson: "What Novell Inc. really is selling is its certified NetWare engineers, instructors, and administrators, and the next release of NetWare." One educational software exec admitted that his company's help line was actually an important profit center. Their main market was the ancillary products they sold for their flagship software, which they had a chance to do while helping customers.

Pinpoint where value is being given out...

...for free now, and then follow up. The next netscape, the next yahoo, the next microsoft is already up and running, and they are giving their stuff away for free. Find them, and hitch your wagon to their star. Look for the following tricks: charges only for ancillaries, as-if-free behavior, memberships, and outright generosity. If they are using the free to play off network effects, they are the real mccoys.

Maximize the value of the network.

Feed the web first. Networks are nurtured by making it as easy as possible to participate. The more diverse the players in your network--competitors, customers, associations, and critics--the better. Becoming a member should be a breeze. You want to know who your customers are, but you don't want to make it hard for them to get to you (IDs, yes; passwords, no). You want to make it easy for your competitors to join too (all their customers could potentially be yours as well). Be open to the power of network effects: Relationships are more powerful than technical quality. Especially beware of the "not-invented-here" syndrome. The surest sign of a great network player is its willingness to let go of its own standard (especially if it is "superior") and adopt someone's else's to leverage the network's effect.

Seek the highest common denominator.

Because of the laws of plentitude and increasing returns, the most valuable innovations are not the ones with the highest performance, but the ones with the highest performance on the widest basis--the "highest per widest." Feeding the web first means ignoring state-of-the-art advances, and choosing instead the highest common denominator--the highest quality that is widely accepted. One practical reason to pick the highest-per-widest techniques and technologies is because complex technologies require passionate and informed users who can share experience and context, and you want the maximum dispersion of usage that doesn't sacrifice quality.

Don't invest in Esperanto.

No matter how superior another way of doing something is, it can't displace an embedded standard--like English. Avoid any scheme that requires the purchase of brand new protocols when usable ones are widely adopted.

Apply an embedded standard in a new territory.

Is there a way to accomplish what you want using existing standards and existing webs in a different context? Inventing a novel standard for an existing network is quixotic. But some of the greatest success stories in current times are about firms that master one network and then use its embedded standards to exploit an established network in need of improvement. This process is called "interfection." The present revolution in telephony is all about zealous internet firms that are interfecting the old Bell-head world of moving voices with newly established protocols for moving data on the internet (known as internet protocols, or IP). The huge increasing returns that spin off the internet give them a great advantage. Indeed, one telephony standard after another is falling before the relentless march of IP. Likewise, aggressive companies are leveraging the established desktop standard of Windows NT--with all its plentitude effects--to interfect new domains such as telephone switching gear. Even the huge cable TV networks have something to offer. The emerging standards for video transmission, such as MPEG, are trying to migrate onto the internet. In choosing which standard to back, consider dominant standards outside your current network that could interfect your own turf.

Animate it.

As the network economy unfolds, more firms will begin to ask themselves this question: How do we put what we do into the logic of networks? How do we prepare a product to behave with network effects? How do we "netize" our product or service? (The answer is not "put it on a web site.") Architects, for instance, generate huge volumes of data. How can they be standardized? How can the data about a physical object (say a door) flow through or with that object? What are the fewest functions we can add to glass windows to incorporate them into networks? What steps can a contractor take to allow the networked flow of information from any architect to any contractor to any builder to any client? How do we increase the number of networks our service embraces?

Side with the net.

Imagine that in 1960 an elf let you in on a secret: For the next 50 years computers would shrink drastically and cheapen yearly on a predictable basis. Subsequently, whenever you needed to make a technological decision, if you had counted on the smaller and cheaper, you would have always been right. Indeed you could have performed financial miracles knowing little more than this rule. Here is today's secret: In the coming 50 years, the net will expand and thicken yearly on a predictable basis--its value growing exponentially as it embraces more members, and its costs of transactions drop toward zero. Whenever you need to make a technological decision, if you err on the side of choosing the more connected, the more open system, the more widely linked standard, you will always be right.

Employ Evangelists.

Economic webs are not alliances. There are often few financial ties among members of a web. An effective way of establishing standards and coordinating development is through evangelists. These are not salespeople, nor executives. Their job is simply to extend the web, to identify others with common interests and then assist in bringing them together. In the early days when Apple was a cocreator of the emerging PC web, it successfully employed evangelists to find third-party vendors to make plug-in boards, or to develop software for their machines. Go and do likewise.

Don't mistake a clear view for a short distance.

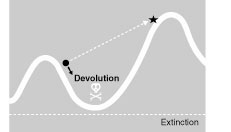

The terror of devolution is that a firm must remain intact while it descends into the harsh deserts between the mountains of successes. It must continue to be more or less profitable while it devolves. You can't jump from peak to peak. No matter how smart or how speedy an organization is, it can't get to where it wants to go unless it muddles across an undesirable place one step at a time. Enduring a period of less than optimal fitness is doubly difficult when a very clear image of the new perfection is in plain sight.

For instance, sometime in the early 1990s the Encyclopaedia Britannica company saw that they were stuck on a local peak. They were at the top: the best encyclopedia in print. They had a worldwide sales force peddling a world-recognized brand. But rising fast nearby was something new: CD-ROM. The outline of this dazzling new mountain was clear. Its height was inspiring. But it was a different realm from their old mountain: no paper, no door-to-door salespeople, cheap, little dinky disks on the shelf, and a media that required constant updates. They would have to undo much of what they knew. Still there, clear as could be, was their future. But while the destination was extremely clear, the path that led to it was treacherous. And, it turned out, the route was even longer than they thought. The company spent millions, lost salespeople in droves, and verged on collapse. They entered a scary period during which neither print nor CD worked. Eventually they completed the CD-ROM encyclopedia they had envisioned many years earlier, but only after an outsider (Microsoft) published a better one. Encyclopaedia Britannica's future is still in doubt. But their travails are common. Says futurist Paul Saffo: "We tend to mistake a clear view of the future for a short distance."

To scale a higher peak -- a potentially greate gain -- often means crossing a valley of less fitness first. A clear view of the future should not be mistaken for a short distance.

Today, nearly everyone in business has a clear view of the future of TV. It's something that comes to you in the same way you get the internet. You choose your shows, from 500 channels. You can shop, maybe interact with a game, or click for more information about a movie you are watching. The technology seems feasible, the physics logical, and the economics plausible. But Future TV looks a lot closer than it really is because the path between here and there winds through a barren desert with little optimal about it. Although the economics may work later, they barely work out now in the alkali flats. It may be that none of the large television or computer or phone companies are sufficiently nimble (or hungry) to make it across the valley of death--even though the shape of success is so visible.

Send the network out.

There is only one sound strategy for crossing the valley: Don't go alone. Established firms are now doing what they should be doing: weaving dozens, if not hundreds, of alliances and partnerships; seeking out as many networks of affiliation and common cause as possible, sharing the risk by making a web. A motley caravan of firms can cross a suboptimal stretch with hope. Banding together buys their networks several things. First, it allows knowledge about the terrain to be shared. Some firm riding point might discover a small hill of opportunity. Settling there allows small oases of opportunity to be created. If enough intermediate oases can be found or made, the long journey can become a series of shorter hops along an archipelago of small successes. The more firms, customers, explorers, and vested interests that are attempting to cross, the more likely the archipelago can be found or created.

To create the future car--a car that is easily imaginable right now--an entrepreneurial car company can only succeed by spinning together a network of vendors, regulators, insurers, road makers, and competitors to help others to devolve quickly and cross.

Who is in charge of devolution?

It is a rare leader who can creatively destroy as well as relentlessly build. It's a rare committee that will vote to terminate what works. It's a rare outsider whose advice to relinquish a golden oldie will be heeded. You are in charge of devolving. Everyone is. It's just one more chore in the network economy.

Question success.

Not every success needs to be abandoned drastically, but every success needs to be questioned drastically. Do interesting substitutes exist? Are radical alternatives receiving compounding attention? You need to consider innovations far afield, ones that are not "on the same mountain." Are there innovations that are changing the rules of the game? Beware of minor incremental improvements--slight baby steps on the same mountain. These can be a form of denial. Nicholas Negroponte, director of the MIT Media Lab, declares "Incrementalism is innovation's worst enemy."

Searching as a way of life.

In the network economy, nine times out of ten, your fiercest competitor will not come from your own field. In turbulent times, when little is locked in, it is imperative to search as wide as possible for places where innovations erupt. Innovations increasingly interfect from other domains. A ceaseless blanket search--wide, easy, and shallow--is the only way you can be sure you will not be surprised. Don't read trade magazines in your field; scan the magazines of other trades. Talk to anthropologists, poets, historians, artists, philosophers. Hire some 17-year-olds to work in your office. Make a habit to visit a web site at random. Tune in to talk radio. Take a class in scenario making. You'll have a much better chance at recognizing the emergence of something important if you treat these remote venues as neighbors.

The only side a network has is outside.

Like a rapidly spinning galaxy, the net creates an unrelenting force that sends everything from the inside toward the outer edges. Since little is left inside, the action is thrown to the perimeter. Rather than buck this centrifugal force, companies should consider outsourcing chores to other equally amorphous networked companies. The most powerful capitulation to the net's outward spin is to outsource seemingly core activities. For instance, some airline companies outsource the business of air-freight hauling, even though the cargo is carried by their own planes. There are 1,001 reasons why core outsourcing can't be done, but 999 of them ignore the centripetal force of the network economy.

Prepare for flash crowds.

Electronic spaces unhinge a crowd of visitors: They can appear in a flash and then leave in a flash. During the chess match between Deep Blue and Gary Kasparov, the IBM web site welcomed 5 million visitors. When the match was over the site was empty. On the eve of the 1996 U.S. elections, the CNN web site experienced 50 million attempts to log on. The next day, the crowd was gone. One day a flash crowd is pounding at the doors, the next day they have vanished. The mass audience has transformed itself into a wave that swishes around from one hot spot to another. But the nature of spaces is that in order to accommodate a flash crowd when they do come, you have to be ready, tooled up.

Skate to the edge of chaos.

Pay the price of radical churn: endorse redundancy, inefficiency, and set the neatniks up in arms. If people are not complaining about how chaotic the place is, you've got a problem. It isn't necessary that the whole organization be in chaos (one hopes the accounting department is spared), but that key parts are. The duty may want to be rotated. Realistically, disequilibrium is very difficult to maintain.

Exploit flux instead of outlawing it.

The traditional practice of telephony tries to eliminate noise and uncertainty by creating an optimally short and uninterrupted circuit between caller and callee. It assumes a stable route. The internet, on the other hand, counts on chaotic change, and it will overtake the entire phone system soon. It sends messages (including voice) in fragmented bits scattered along redundant routes, and then resends whatever the haphazard process loses to noisy lines. Rather than prohibit errors, network logic assumes errors and learns from the chaotic flux. Find where the flux is, and ride it.

You can't install complexity.

Networks are biased against large-scale drastic change. The only way to implement a large new system is to grow it. You can't install it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia tried to install capitalism, but this complex system couldn't be installed; it had to be grown. The network economy favors assembling large organizations from many smaller ones that keep their autonomy within the large. Networks, too, need to be grown, rather than installed. They need to accumulate over time. To grow a large network, one needs to start with a small network that works, then add more sophisticated nodes and levels to it. Every successful large system was once a successful small system.

Preserve the core, and let the rest flux.

In their wonderful bestseller Built to Last, authors James Collins and Jerry Porras make a convincing argument that long-lived companies are able to thrive 50 years or more by retaining a very small heart of unchanging values, and then stimulating progress in everything else. At times "everything" includes changing the business the company operates in, migrating, say, from mining to insurance. Outside the core of values, nothing should be exempt from flux. Nothing.

Make customers as smart as you are.

For every effort a firm makes in educating itself about the customer, it should expend an equal effort in educating the customer. It's a tough job being a consumer these days. Any help will be rewarded by loyalty. If you don't educate your customer, someone else will--most likely someone not even a competitor. Almost any technology that is used to market to customers, such as data mining, or one-to-one techniques, can be flipped around to provide intelligence to the customer. No one is eager for a core dump, but if you can remember my trouser size, or suggest a movie that all my friends loved, or sort out my insurance needs, then you are making me smarter. The rule is simple: Whoever has the smartest customers wins.

Connect customers to customers.

Nothing is as scary to many corporations as the idea of sponsoring dens in which customers can talk to one another. Especially if it is an effective place of communication. Like the web. "You mean," they ask in wonder, "we should pay a million dollars to develop a web site where customers can swap rumors and make a lot of noise? Where complaints will get passed around and the flames of discontent fanned?" Yes, that's right. Often that's what will happen. "Why should we pay our customers to harass us," they ask, "when they will do that on their own?" Because there is no more powerful force in the network economy than a league of connected customers. They will teach you faster than you could learn any other way. They will be your smartest customers, and, to repeat, whoever has the smartest customers wins.

Just recently E-trade, the pioneering online stock broker, took the bold step of setting up an online chat area for its customers. We'll see more smart companies do this. Whatever tools you develop that will aid the creation of relationships between your customers will strengthen the relationship of your customers to you. This effort can also be thought of as Feeding the Web First.

All things being equal, choose technology...

...that connects. Technology tradeoffs are made daily. A device or method cannot be the fastest, cheapest, more reliable, most universal, and smallest all at once. To excel, a tech has to favor some dimensions over others. Now add to that list, most connected. This aspect of technology has increasing importance, at times overshadowing such standbys as speed and price. If you are in doubt about what technology to purchase, get the stuff that will connect the most widely, the most often, and in the most ways. Avoid anything that resembles an island, no matter how well endowed that island is.

Imagine your customers as employees.

It is not a cheap trick to get the customer to do what employees used to do. It's a way to make a better world! I believe that everyone would make their own automobile if it was easy and painless. It's not. But customers at least want to be involved at some level in the creation of what they use--particularly complex things they use often. They can superficially be involved by visiting a factory and watching their car being made. Or they can conveniently order a customized list of options. Or, through network technology, they can be brought into the process at various points. Perhaps they send the car through the line, much as one follows a package through FedEx. Smart companies have finally figured out that the most accurate way to get customer information, such as a simple address, without error, is to have the customer type it themselves right from the first. The trick will be finding where the limits of involvement are. Customers are a lot harder to get rid of than employees! Managing intimate customers requires more grace and skill than managing staff. But these extended relationships are more powerful as well.

The final destiny for the future of the company often seems to be the "virtual corporation"--the corporation as a small nexus with essential functions outsourced to subcontractors. But there is an alternative vision of an ultimate destination--the company that is only staffed by customers. No firm will ever reach that extreme, but the trajectory that leads in that direction is the right one, and any step taken to shift the balance toward relying on the relationships with customers will prove to be an advantage.

Why can't a machine do this?

If there is pressure to increase the productivity of human workers, the serious question to ask is, why can't a machine do this? The fact that a task is routine enough to be measured suggests that it is routine enough to go to the robots. In my opinion, many of the jobs that are being fought over by unions today are jobs that will be outlawed within several generations as inhumane.

Scout for upside surprises.

The qualities needed to succeed in the network economy can be reduced to this: a facility for charging into the unknown. Disaster lurks everywhere, but so do unexpected bonanzas. But the Great Asymmetry ensures that the upside potential outweighs the downside, even though nine out of ten tries will fail. Upside benefits tend to cluster. When there are two, there will be more. A typical upside surprise is an innovation that satisfies three wants at once, and generates five new ones, too.

Maximize the opportunity cascade.

One opportunity triggers another. And then another. That's a rifle-shot opportunity burst. But if one opportunity triggers ten others and those ten others after, it's an explosion that cascades wide and fast. Some seized opportunities burst completely laterally, multiplying to the hundreds of thousands in the first generation--and then dry up immediately. Think of the pet rock. Sure, it sold in the millions, but then what? There was no opportunity cascade. The way to determine the likelihood of a cascade is to explore the question: How many other technologies or businesses can be started by others based on this opportunity?

New Rules for the New Economy

1) Embrace the Swarm. As power flows away from the center, the competitive advantage belongs to those who learn how to embrace decentralized points of control.

2) Increasing Returns. As the number of connections between people and things add up, the consequences of those connections multiply out even faster, so that initial successes aren't self-limiting, but self-feeding.

3) Plentitude, Not Scarcity. As manufacturing techniques perfect the art of making copies plentiful, value is carried by abundance, rather than scarcity, inverting traditional business propositions.

4) Follow the Free. As resource scarcity gives way to abundance, generosity begets wealth. Following the free rehearses the inevitable fall of prices, and takes advantage of the only true scarcity: human attention.

5) Feed the Web First. As networks entangle all commerce, a firm's primary focus shifts from maximizing the firm's value to maximizing the network's value. Unless the net survives, the firm perishes.

6) Let Go at the Top. As innovation accelerates, abandoning the highly successful in order to escape from its eventual obsolescence becomes the most difficult and yet most essential task.

7) From Places to Spaces. As physical proximity (place) is replaced by multiple interactions with anything, anytime, anywhere (space), the opportunities for intermediaries, middlemen, and mid-size niches expand greatly.

8) No Harmony, All Flux. As turbulence and instability become the norm in business, the most effective survival stance is a constant but highly selective disruption that we call innovation.

9) Relationship Tech. As the soft trumps the hard, the most powerful technologies are those that enhance, amplify, extend, augment, distill, recall, expand, and develop soft relationships of all types.

10) Opportunities Before Efficiencies. As fortunes are made by training machines to be ever more efficient, there is yet far greater wealth to be had by unleashing the inefficient discovery and creation of new opportunities.