8: NO HARMONY, ALL FLUX

Seeking Sustainable Disequilibrium

In the industrial perspective, the economy was a machine that was to be tweaked to optimal efficiency, and once finely tuned, maintained in productive harmony. Companies or industries especially productive of jobs or goods had to be protected and cherished at all costs, as if these firms were rare watches in a glass case.

As networks have permeated our world, the economy has come to resemble an ecology of organisms, interlinked and coevolving, constantly in flux, deeply tangled, ever expanding at its edges. As we know from recent ecological studies, no balance exists in nature; rather, as evolution proceeds, there is perpetual disruption as new species displace old, as natural biomes shift in their makeup, and as organisms and environments transform each other.

Even the archetypal glories of hardwood forests or coastal wetlands, with their apparent wondrous harmony of species, are temporary federations on the move. Harmony in nature is fleeting. Over relatively short periods of biological time, the mix of species churns, the location of ecosystems drift, and the roster of animals and plants changes as they come and go.

So it is with network perspective: companies come and go quickly, careers are patchworks of vocations, industries are indefinite groupings of fluctuating firms.

Change is no stranger to the industrial economy or the embryonic information economy; Alvin Toffler coined the term "future shock" in 1970 as the reasonable response of humans to an era of accelerating change.

But the network economy has moved...

...from change to flux.

Change, even in its shocking forms, is rapid difference. Flux, on the other hand, is more like the Hindu god Shiva, a creative force of destruction and genesis. Flux topples the incumbent and creates a platform for more innovation and birth. This dynamic state might be thought of as "compounded rebirth." And its genesis hovers on the edge of chaos.

Donald Hicks of the University of Texas studied the half-life of Texan businesses for the past 22 years and found that their longevity has dropped by half since 1970. That's change. But Austin, the city in Texas in which new businesses have the shortest expected life spans, also has the fastest-growing number of new jobs and the highest wages. That's flux.

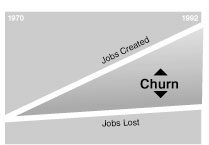

The number of old jobs lost increases, but not as fast as the number of new jobs created. More important, the spread of gained jobs over lost jobs widens.

Hicks told his sponsors in Texas that "the vast majority of the employers and employment on which Texans will depend in the year 2026--or even 2006--do not yet exist." In order to produce 3 million new jobs by 2020, 15 million new jobs must be created in all, because of flux. "Rather than considering jobs as a fixed sum to be protected and augmented, Hicks argued, the state should focus on encouraging economic churning--on continually recreating the state's economy," writes Jerry Useem in Inc., a small-business magazine that featured Hick's report. Ironically, only by promoting flux can long-term stability be achieved.

When flux is inhibited...

...slow death takes over. Contrast Texas and the other 49 states with the European Union. Between 1980 and 1995 Europe protected 12 million governmental jobs, and in the process of fostering stasis lost 5 million jobs in the private sector. The United States, fostering flux, saw a staggering 44 million old jobs disappear from the private sector. But 73 million new jobs were generated, for a net gain of 29 million, and in the process the United States kept its 12 million government jobs, too. If you can stand the turmoil, flux triumphs.

This notion of constant flux is familiar to ecologists and those who manage large networks. The sustained vitality of a complex network requires that the net keep provoking itself out of balance.

Nowhere is this trend toward constant flux...

...more evident than in the entertainment industry centered in southern California. Hollywood's "cultural-industrial complex" includes not just film, but also music, multimedia, theme park design, TV production, and commercials.

Giant film studios no longer make movies. Loose entrepreneurial networks of small firms make movies, which appear under the names of the big studios. In addition to various camera crews, about 40 to 50 other firms, plus scores of freelancers, connect up to produce a movie; these include special effects vendors, prop specialists, lighting technicians, payroll agencies, security folks, and catering firms. They convene as one financial organization for the duration of the movie project, and then when the movie is done, the company disperses. Not too much later they will reconvene as other movie-making entities in entirely new ad hoc arrangements. Cyberpunk author Bruce Sterling has his own inimitable way of describing the flux of "Hollywood film ad-hocracies." To make a movie, he says, "You're pitchforking a bunch of freelancers together, exposing some film, using the movie as the billboard to sell the ancillary rights, and after the thing gets slotted to video, everybody just vanishes."

Fewer than ten entertainment companies employ more than 1,000 employees. Of the 250,000 people involved in the entertainment complex in the Los Angeles region, an estimated 85% of the firms employ 10 people or fewer. Joel Kotkin, author of a landmark 1995 article in Inc. magazine entitled, "Why Every Business Will Be Like Show Business," writes: "Hollywood has mutated from an industry of classic huge, vertically integrated corporations into the world's best example of a network economy. Eventually, every knowledge-intensive industry will end up in the same flattened, atomized state. Hollywood just has gotten there first."

If the system settles into harmony and equilibrium...

...it will eventually stagnate and die.

Innovation is disruption; constant innovation is perpetual disruption. This seems to be the goal of a well-made network: to sustain a perpetual disequilibrium. A few economists studying the new economy (among them Paul Romer and Brian Arthur) have come to similar conclusions. Their work suggests that robust growth sustains itself by poising on the edge of constant chaos. "If I have had a constant purpose it is to show that transformation, change, and messiness are natural in the economy," writes Arthur.

The difference between chaos and the edge of chaos is subtle. Apple Computer, in its attempt to seek persistent disequilibrium and stay innovative, may have tottered too far off-balance and let itself unravel toward extinction. Or, if its luck holds, it may discover a new mountain to ascend after a near-death experience.

The dark side of flux is that the new economy builds on the constant extinction of individual companies as they're outpaced or morphed into yet newer companies in new fields. Industries and occupations also experience this churn. Even a sequence of rapid job changes for workers--let alone lifetime employment--is on its way out. Instead, careers--if that is the word for them--will increasingly resemble networks of multiple and simultaneous commitments with a constant churn of new skills and outmoded roles. About 20% of the American workforce already have an arrangement other than the traditional employee relationship with one employer. And 86% of them claim to be happy about it.

Silicon Valley is not far behind.

The ICE businesses--information, communication, and entertainment--all rely on speed and flexibility to survive in a self-made speedy and flexible environment. Things move so fast that even a corporation--any corporation--seems too rigid and staid. You can't alter bureaucratic structure fast enough, so don't even build one to begin with.

Networks are immensely turbulent and uncertain. The prospect of constantly tearing down what is now working will make future shock seem tame. As creatures of habit we will challenge the need to undo established successes. We are sure to find exhausting the constant, fierce birthing of so much that is new. The network economy is so primed to generate self-making newness that we may experience this ceaseless tide of birth as a type of violence.

In a poetic sense, the prime goal...

...of the new economy is to undo--company by company, industry by industry--the industrial economy.

In reality, of course, the industrial cortex cannot be undone. But a larger web of new, more agile, more tightly linked organizations can be woven around it. These upstart firms bank on constant change and flux.

Change itself is no news, however. Ordinary change triggers yawns. Most change is mere churn, a random disposable newness that accomplishes little. Churn is the status quo for these times. At the other extreme, there is change so radical that it topples the tower. Like inventions that fail because they are way ahead of their times, it is possible to reach too far with change.

What the network economy coaxes forth is a selective flux. The right kind of change, in the right doses. In almost all respects this kind of change is what we mean by innovation.

The word "innovation" is so common now that its true meaning is hidden. A truly innovative step is neither too staid and obvious, nor too far out. The innovative step is change that is neither random directionless churn, nor so outrageous that it can't be appreciated. We wouldn't properly call just another variation of something an innovation. We also wouldn't call a shift to something that only worked in theory, but not practice, or that required a massive change in everyone else's behavior to work, an innovation.

A real innovation is sufficiently different to be dangerous. It is change just this side of being ludicrous. It skirts the edge of the disaster, without going over. Real innovation is scary. It is anything but harmonious.

The selective flux of innovation...

...permeates the network economy the way efficiency permeated the industrial economy. The innovative flux is not merely dedicated to devising more interesting products, although that is its everyday chore. Innovation and flux saturate the entire emerging space of the new economy. Innovation premiers in:

New products

New categories of products

New methods to make old and new products

New types of organizations to make products

New industries

New economies

All of these will twist and turn as change, dangerous change, spirals through them. This is why there is such a maniacal fuss about innovation. When management gurus drone on about the imperative of innovation, they are right. Firms still need excellence, quality of service, reorganization, and real time, but nothing quite embodies the ultimate long-term task in this new economy as the tornado of innovation.

Because large systems must tread a path between the ossification of order and the destruction of chaos, networks tend to be in a constant state of turmoil and flux.

This is where life lives, between the rigid death...

...of planned order and the degeneration of chaos. Too much change can get out of hand, and too many rules--even new rules--can lead to paralysis. The best systems have this living quality of few rules and near chaos. There is enough binding agreement between members that they don't fall into anarchy, yet redundancy, waste, incomplete communications, and inefficiency are rife.

My own involvement in groups that launched successful change, and my secondhand knowledge of many, many others involved in world-changing innovation, convinces me that all of these ensembles teetered on the brink of chaos at their peak performance. Whatever front they put up to the public or investors, behind the scenes most of the group ran around screaming "It's pathologically out of control here!" Every organization is dysfunctional to some degree, but innovative organizations, in their moment of glory, tend to slide toward uncoordinated communication, furious bouts of genius, and life-threatening disorganization. Everyone involved swears they will institute just enough structure to prevent flameout in the future, but I've never seen radical innovation emerge from an outfit that wasn't halfway to unraveling at the epicenter of change. Most of the studies of optimal evolution in complex systems confirm this view. The price for progressive change in maximum doses is a dangerous (and thrilling) ride to the edge of disruption.

Although many groups experience these grand moments when creativity flows and things get done well, the holy grail in business and life is to find ways to sustain these periods of supreme balance. Sustaining innovation is particularly tricky since it flows out of creative disequilibrium.

To achieve sustainable innovation...

you need to seek persistent disequilibrium. To seek persistent disequilibrium means that one must chase after disruption without succumbing to it, or retreating from it.

A company, institution, or individual must remain perched in an almost-falling state. In this precarious position it is inclined to fall, but continually catches itself and never quite topples. Nor does it anchor itself so that it cannot tip. It sort of skips along within reach of disaster, but uses the power of falling to propel itself forward with grace. A lot of people compare it to surfing; you ride a wave, which is constantly tumbling, and perched on top of this continually disintegrating hill of water, you harness its turbulence into forward motion.

Innovation is hard to institutionalize. It often needs to bend the rules of its own creation. Indeed, by definition innovation means to break away from established patterns, which means that it tends to jump over formulas. In periods of severe flux, such as the transition we are now in between a resource-based economy and a connected-knowledge one, change enters other levels.

Change comes in various wavelengths.

There are changes in the game, changes in the rules of the game, and changes in how the rules are changed.

The first level--changes in the game--produces the kind of changes now visible: new winners and losers. New businesses. New heroes. We see the rise of Wal-Marts, and of Nucor steelmaking.

The second level--changes in the rules of the game--produces new kinds of business, new sectors of the economy, new kinds of games. From this type of change comes the Microsofts and Amazon.coms.

The third level of change, which we are now entering, whips up changes in how change happens. Change changes itself. While the new economy provokes change in the first two levels--all those new business and business sectors--its deepest consequence is the way it alters change. Change accelerates itself. It morphs into creative destruction. It induces flux. It disperses into a field effect, so you can't pinpoint causes. It overturns the old ways of change.

Change in technological systems is becoming...

...more biological. This will take a lot of getting used to. Networks actually grow. Evolution can really be imported into machines. Technological immune systems can be used to control computer viruses. This neobiologicalism seeps directly into our new economy. More and more, biological metaphors are useful economic metaphors.

The image of the economy as something alive is powerful. And it is hardly New Age hokum. Adam Smith himself alluded to aliveness with his unseen "hand." Karl Marx often referred to the organic nature of the economy. Even the legendary no-nonsense economist Alfred Marshall wrote in 1948 that "the Mecca of the economist lies in economic biology." Marshall was writing at the peak of the industrial economy. The first stirrings of the coming power of information were just being felt.

Living systems are notoriously hard to model and theorize about, and even more difficult to predict. Until very recently economics has gravitated to an understanding that settled on an equilibrium, primarily because anything more complex was impossible to calculate. Ironically, the very same computer technology, which has roused flux in the economy, is now used to model it. With powerful chips, dynamic, learning, self-feeding theories of the economy can be mapped out.

Both in our understanding of it, and in reality, the network economy is a place that harbors little harmony or stasis. Instead, it is a system that will increasingly demand flux and innovation. The art of judicious change, of the dangerous difference, will be rewarded in full.

Skate to the edge of chaos.

Pay the price of radical churn: endorse redundancy, inefficiency, and set the neatniks up in arms. If people are not complaining about how chaotic the place is, you've got a problem. It isn't necessary that the whole organization be in chaos (one hopes the accounting department is spared), but that key parts are. The duty may want to be rotated. Realistically, disequilibrium is very difficult to maintain.

Exploit flux instead of outlawing it.

The traditional practice of telephony tries to eliminate noise and uncertainty by creating an optimally short and uninterrupted circuit between caller and callee. It assumes a stable route. The internet, on the other hand, counts on chaotic change, and it will overtake the entire phone system soon. It sends messages (including voice) in fragmented bits scattered along redundant routes, and then resends whatever the haphazard process loses to noisy lines. Rather than prohibit errors, network logic assumes errors and learns from the chaotic flux. Find where the flux is, and ride it.

You can't install complexity.

Networks are biased against large-scale drastic change. The only way to implement a large new system is to grow it. You can't install it. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia tried to install capitalism, but this complex system couldn't be installed; it had to be grown. The network economy favors assembling large organizations from many smaller ones that keep their autonomy within the large. Networks, too, need to be grown, rather than installed. They need to accumulate over time. To grow a large network, one needs to start with a small network that works, then add more sophisticated nodes and levels to it. Every successful large system was once a successful small system.

Preserve the core, and let the rest flux.

In their wonderful bestseller Built to Last, authors James Collins and Jerry Porras make a convincing argument that long-lived companies are able to thrive 50 years or more by retaining a very small heart of unchanging values, and then stimulating progress in everything else. At times "everything" includes changing the business the company operates in, migrating, say, from mining to insurance. Outside the core of values, nothing should be exempt from flux. Nothing.