Making the Inevitable Obvious

101 Additional Advices

Six years ago I celebrated my 68th birthday by gifting my children 68 bits of advice I wished I had gotten when I was their age. Every birthday after that I added more bits of advice for them until I had a whole book of bits. That book was published a year ago as Excellent Advice for Living, which many people tell me they read very slowly, just one bit per day. In a few days I will turn 73, so again on my birthday, I offer an additional set of 101 bits of advice I wished I had known earlier. None of these appear in the book; they are all new. If you enjoy these, or find they resonate with your own experience, there are 460 more bits in my Excellent Advice book, all neatly bound between hard covers, in a handy size, ready to gift to a person younger than yourself. – KK

• The best way to criticize something is to make something better.

• Admitting that “I don’t know” at least once a day will make you a better person.

• Forget trying to decide what your life’s destiny is. That’s too grand. Instead, just figure out what you should do in the next 2 years.

• Aim to be effective, but unpredictable. That is, you want to act in a way that AIs have trouble modeling or imitating. That makes you irreplaceable.

• Whenever you hug someone, be the last to let go.

• Don’t save up the good stuff (fancy wine, or china) for that rare occasion that will never happen; instead use them whenever you can.

• The best gardening advice: find what you can grow well and grow lots and lots of it.

• Never hesitate to invest in yourself—to pay for a class, a course, a new skill. These modest expenditures pay outsized dividends.

• Try to define yourself by what you love and embrace, rather than what you hate and refuse.

• Read a lot of history so you can understand how weird the past was; that way you will be comfortable with how weird the future will be.

• To make a room luxurious, remove things, rather than add things.

• Interview your parents while they are still alive. Keep asking questions while you record. You’ll learn amazing things. Or hire someone to make their story into an oral history, or documentary, or book. This will be a tremendous gift to them and to your family.

• If you think someone is normal, you don’t know them very well. Normalcy is a fiction. Your job is to discover their weird genius.

• When shopping for anything physical (souvenirs, furniture, books, tools, shoes, equipment), ask yourself: where will this go? Don’t buy it unless there is a place it can live. Something may need to leave in order for something else to come in.

• You owe everyone a second chance, but not a third.

• When someone texts you they are running late, double the time they give you. If they say they’ll be there in 5, make that 10; if 10, it’ll be 20; if 20, count on 40.

• Multitasking is a myth. Don’t text while walking, running, biking or driving. Nobody will miss you if you just stop for a minute.

• You can become the world’s best in something primarily by caring more about it than anyone else.

• Asking “what-if?” about your past is a waste of time; asking “what-if?” about your future is tremendously productive.

• Try to make the kind of art and things that will inspire others to make art and things.

• Once a month take a different route home, enter your house by a different door, and sit in a different chair at dinner. No ruts.

• Where you live—what city, what country—has more impact on your well being than any other factor. Where you live is one of the few things in your life you can choose and change.

• Every now and then throw a memorable party. The price will be steep, but long afterwards you will remember the party, whereas you won’t remember how much is in your checking account.

• Most arguments are not really about the argument, so most arguments can’t be won by arguing.

• The surest way to be successful is to invent your own definition of success. Shoot your arrows first and then paint a bull’s eye around where they land. You’re the winner!

• When remodeling a home interior use big pieces of cardboard to mock-up your alterations at life size. Seeing things, such as counters, at actual size will change your plans, and it is so much easier to make modifications with duct tape and scissors.

• There should be at least one thing in your life you enjoy despite being no good at it. This is your play time, which will keep you young. Never apologize for it.

• Changing your mind about important things is not a consequence of stupidity, but a sign of intelligence.

• You have 5 minutes to act on a new idea before it disappears from your mind.

• What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important. To get the important stuff done, avoid the demands of the urgent.

• Three situations where you’ll never regret ordering too much: when you are pouring concrete, when you are choosing a battery, and when you are getting ice for a party.

• The patience you need for big things, is developed by your patience with the little things.

• Don’t fear failure. Fear average.

• When you are stuck or overwhelmed, focus on the smallest possible thing that moves your project forward.

• In a museum you need to spend at least 10 minutes with an artwork to truly see it. Aim to view 5 pieces at 10 minutes each rather than 100 at 30 seconds each.

• For steady satisfaction, work on improving your worst days, rather than your best days.

• Your decisions will become wiser when you consider these three words: “…and then what?” for each choice.

• If possible, every room should be constructed to provide light from two sides. Rooms with light from only one side are used less often, so when you have a choice, go with light from two sides.

• Never accept a work meeting until you’ve seen the agenda and know what decisions need to be made. If no decisions need to be made, skip the meeting.

• You have no obligation to like everyone, and you are free to intensely dislike a person. But you owe everyone—even those you dislike—basic respect.

• When you find yourself procrastinating, don’t resist. Instead lean into it. Procrastinate 100%. Try to do absolutely nothing for 5 minutes. Make it your job. You’ll fail. After 5 minutes, you’ll be ready and eager to work.

• If you want to know how good a surgeon is, don’t ask other doctors. Ask the nurses.

• There is a profound difference between thinking less of yourself (not useful), and thinking of yourself less (better).

• Strong opinions, clearly stated, but loosely held is the recipe for an intellectual life. Always ask yourself: what would change my mind?

• You can not truly become yourself, by yourself. Becoming one-of-a-kind is not a solo job. Paradoxically you need everyone else in the world to help make you unique.

• If you need emergency help from a bystander, command them what to do. By giving them an assignment, you transform them from bewildered bystander to a responsible assistant.

• The most common mistake we make is to do a great job on an unimportant task.

• Don’t work for a company you would not invest money in, because when you are working you are investing the most valuable thing you have: your time.

• Fail fast. Fail often. Fail forward. Failing is not a disgrace if you keep failing better.

• Doing good is its own reward. When you do good, people will question your motive, and any good you accomplish will soon be forgotten. Do good anyway.

• Best sleep aid: first, get really tired.

• For every success there is a corresponding non-monetary tax of some kind. To maintain success you have to gladly pay these taxes.

• Do not cling to a mistake just because you spent a lot of time making it.

• For small tasks the best way to get ready is to do it immediately.

• If someone is calling you to alert you to fraud, nine out of ten times they are themselves the fraudster. Hang up. Call the source yourself if concerned.

• When you try to accomplish something difficult, surround yourself with friends.

• You should be willing to look foolish at first, in order to look like a genius later.

• Think in terms of decades, and act in terms of days.

• The most selfish thing in the world you can do is to be generous. Your generosity will return you ten fold.

• Discover people whom you love doing “nothing” with, and do nothing with them on a regular basis. The longer you can maintain those relationships, the longer you will live.

• Forget diamonds; explore the worlds hidden in pebbles. Seek the things that everyone else ignores.

• Write your own obituary, the one you’d like to have, and then everyday work towards making it true.

• Avoid making any kind of important decision when you are either hungry, angry, lonely, or tired (HALT). Just halt when you are HALT.

• What others want from you is mostly to be seen. Let others know you see them.

• Working differently is usually more productive than working harder.

• When you try something new, don’t think of it as a matter of success / failure, but as success / learning to succeed.

• If you have a good “why” to live for, no “how” will stop you.

• If you are out of ideas, go for a walk. A good walk empties the mind—and then refills it with new stuff.

• The highest form of wealth is deciding you have enough.

• Education is overly expensive. Gladly pay for it anyway, because ignorance is even more expensive.

• The cheapest therapy is to spend time with people who make you laugh.

• Always be radically honest, but use your honesty as a gift not as a weapon. Your honesty should benefit others.

• A good sign that you are doing the kind of work you should be doing is that you enjoy the tedious parts that other people find tortuous.

• Being envious is a toxin. Instead take joy in the success of others and treat their success as your gain. Celebrating the success of others costs you nothing, and increases the happiness of everyone, including you.

• The more persistent you are, the more chances you get to be lucky.

• To tell a good story, you must reveal a surprise; otherwise it is just a report.

• Small steps matter more when you play a long game because a long horizon allows you to compound small advances into quite large achievements.

• If you are more fortunate than others, build a longer table rather than a taller fence.

• Many fail to finish, but many more fail to start. The hardest work in any work is to start. You can’t finish until you start, so get good at starting.

• Work on your tone. Often ideas are rejected because of the tone of voice they are wrapped in. Humility covers many blemishes.

• When you are right, you are learning nothing.

• Very small things accumulate until they define your larger life. Carefully choose your everyday things.

• It is impossible to be curious and furious at the same time, so avoid furious.

• College is not about grades. No one cares what grades you got in college. College is about exploring. Just try stuff.

• Weird but true: If you continually give, you will continually have.

• To clean up your city, sweep your doorstep first.

• Decisions like to present themselves as irreversible, like a one-way door. But most deciding points are two-way. Don’t get bogged down by decisions. You can usually back up if needed.

• Every mistake is an opportunity to improvise.

• You’ll never meet a very successful pessimistic person. If you want to be remarkable, get better at being optimistic.

• You can’t call it charity unless no one is watching.

• When you think of someone easy to despise—a tyrant, a murderer, a torturer—don’t wish them harm. Wish that they welcome orphans into their home, and share their food with the hungry. Wish them goodness, and by this compassion you will increase your own happiness.

• Get good at being corrected without being offended.

• The week between Christmas and New Years was invented to give you the perfect time to sharpen your kitchen knives, vacuum your car, and tidy the folders on your desktop.

• There is no formula for success, but there are two formulas for failure: not trying and not persisting.

• We tend to overrate the value of intelligence.You need to pair your IQ with other virtues. The most important things in life can not be attained through logic only.

• If you are impressed with someone’s work, you should tell them, but even better, tell their boss.

• In matters of the heart, one moment of patience can save you years of regret.

• Humility is mostly about being very honest about how much you owe to luck.

• Slow progress is still a million times better than no progress.

• Recipe for greatness: expect much of yourself and little of others.

• The very best way to win a friend is to be one.

Weekly Links, 03/22/2024

- Drones in warfare are rapidly reshaping modern war. Quick summary here: Drone Swarms Are About to Change the Balance of Military Power

Weekly Links, 03/08/2024

- Could a rogue billionaire build a nuke? Yes, said a Pentagon study last decade. Good story here: Could a Rogue Billionaire Make a Nuclear Weapon?

Type 2 Growth

While technology has gotten us into this climate change mess only technology can get us out of it. Only the technium (our technological system) is “big” enough to work at the global scale needed to fix this planetary sized problem. Individual personal virtue (bicycling, using recycling bins) is not enough. However the worry of some environmentalists is that technology can only contribute more to the problem and none to the solution. They believe that tech is incapable of being green because it is the source of relentless consumerism at the expense of diminishing nature, and that our technological civilization requires endless growth to keep the system going. I disagree.

In English there is a curious and unhelpful conflation of the two meanings of the word “growth.” The most immediate meaning is to increase in size, or increase in girth, to gain in weight, to add numbers, to get bigger. In short, growth means “more.” More dollars, more people, more land, more stuff. More is fundamentally what biological, economic, and technological systems want to do: dandelions and parking lots tend to fill all available empty places. If that is all they did, we’d be well to worry. But there is another equally valid and common use of the word “growth” to mean develop, as in to mature, to ripen, to evolve. We talk about growing up, or our own personal growth. This kind of growth is not about added pounds, but about betterment. It is what we might call evolutionary or developmental, or type 2 growth. It’s about using the same ingredients in better ways. Over time evolution arranges the same number of atoms in more complex patterns to yield more complex organisms, for instance producing an agile lemur the same size and weight as a jelly fish. We seek the same shift in the technium. Standard economic growth aims to get consumers to drink more wine. Type 2 growth aims to get them to not drink more wine, but better wine.

The technium, like nature, excels at both meanings of growth. It can produce more, rapidly, and it can produce better, slowly. Individually, corporately and socially, we’ve tended to favor functions that produce more. For instance, to measure (and thus increase) productivity we count up the number of refrigerators manufactured and sold each year. More is generally better. But this counting tends to overlook the fact that refrigerators have gotten better over time. In addition to making cold, they now dispense ice cubes, or self-defrost, and use less energy. And they may cost less in real dollars. This betterment is truly real value, but is not accounted for in the “more” column. Indeed a tremendous amount of the betterment in our lives that is brought about by new technology is difficult to measure, even though it feels evident. This “betterment surplus” is often slow moving, wrapped up with new problems, and usually appears in intangibles, such as increased options, safety, choices, new categories, and self actualization — which like most intangibles, are very hard to pin down. The benefits only become more obvious when we look back in retrospect to realize what we have gained. Part of our growth as a civilization is moving from a system that favors more barrels of wine, to one that favors the same barrels of better wine.

A major characteristic of sapiens has been our compulsion to invent things, which we have been doing for tens of thousands of years. But for most of history our betterment levels were flatlined, without much evidence of type 2 growth. That changed about 300 years ago when we invented our greatest invention — the scientific method. Once we had hold of this meta-invention we accelerated evolution. We turned up our growth rate in every dimension, inventing more tools, more food, more surplus, more population, more minds, more ideas, more inventions, in a virtuous spiral. Betterment began to climb. For several hundred years, and especially for the last hundred years, we experience steady betterment. But that betterment — the type 2 growth — has coincided with massive expansion of “moreness.” We’ve exploded our human population by an order of magnitude, we’ve doubled our living space per person, we have rooms full of stuff our ancestors did not. Our betterment, that is our living standards, have increased alongside the expansion of the technium and our economy, and most importantly the expansion of our population. There is obviously some part of a feedback loop where increased living standards enables yearly population increases and more people create the technology for higher living standards, but causation is hard to parse. What we can say for sure is that as a species we don’t have much experience, if any, with increasing living standards and fewer people every year. We’ve only experience increased living standards alongside of increased population.

By their nature demographic changes unroll slowly because they run on generational time. Inspecting the demographic momentum today it is very clear human populations are headed for a reversal on the global scale by the next generation. After a peak population around 2070, the total human population on this planet will start to diminish each year. So far, nothing we have tried has reversed this decline locally. Individual countries can mask this global decline by stealing residents from each other via immigration, but the global total matters for our global economy. This means that it is imperative that we figure out how to shift more of our type 1 growth to type 2 growth, because we won’t be able to keep expanding the usual “more.” We will have to perfect a system that can keep improving and getting better with fewer customers each year, smaller markets and audiences, and fewer workers. That is a huge shift from the past few centuries where every year there has been more of everything.

In this respect “degrowthers” are correct in that there are limits to bulk growth — and running out of humans may be one of them. But they don’t seem to understand that evolutionary growth, which includes the expansion of intangibles such as freedom, wisdom, and complexity, doesn’t have similar limits. We can always figure out a way to improve things, even without using more stuff — especially without using more stuff! There is no limit to betterment. We can keep growing (type 2) indefinitely.

The related concern about the adverse impact of the technology on nature is understandable, but I believe, can also be solved. The first phases of agriculture and industrialization did indeed steamroll forests and wreck ecosystems. Industry often required colossal structures of high-temperature, high pressure operations that did not operate at human or biological scale. The work was done behind foot-thick safety walls and chain link fences. But we have “grown.” We’ve learned the importance of the irreplaceable subsidy nature provides our civilizations and we have begun to invent more suitable technologies. Industrial-strength nuclear fission power will eventually give way to less toxic nuclear fusion power. The work of this digital age is more accommodating to biological conditions. As kind of a symbolic example, the raw ingredients for our most valuable products, like chips, require ultra cleanliness, and copious volumes of air and water cleaner than we’d ever need ourselves. The tech is becoming more aligned with our biological scale. In a real sense, much of the commercial work done today is not done by machines that could kill us, but by machines we carry right next to our skin in our pockets. We continue to create new technologies that are more aligned with our biosphere. We know how to make things with less materials. We know how to run things with less energy. We’ve invented energy sources that reduce warming. So far we’ve not invented any technology that we could not successfully make more green.

We have a ways to go before we implement these at scale, economically, with consensus. And it is not inevitable at all that we will grab the political will to make these choices. But it is important to realize that the technium is not inherently contrary to nature; it is inherently derived from evolution and thus inherently capable of being compatible with nature. We can choose to create versions of the technium that are aligned with the natural world. Or not. As a radical optimist, I work towards a civilization full of life-affirming high technology, because I think this is possible, and by imagining “what could be” gives us a much greater chance of making it real.

[This essay began as a response in an email interview with Noah Smith, published in his newsletter, here. His newsletter is great; I am a paying subscriber.]

Weekly Links, 03/01/2024

- We are inching closer to being able to communicate in language with animals. Whales may be first. What do we want to say when we do talk to them? HOW FIRST CONTACT WITH WHALE CIVILIZATION COULD UNFOLD

Weekly Links, 02/23/2024

- The latest way for scammers is to convince you they are fraud police protecting you. They may even have your social security, etc. Don’t cooperate with anyone who calls you. You need to call them. Here is long story of a business columnist who was scammed. The Day I Put $50,000 in a Shoe Box and Handed It to a Stranger I never thought I was the kind of person to fall for a scam.

Rights / Responsibilities

We tend to talk about rights without ever mentioning their corresponding duties. Every right needs an obligation to support it. At the very least we have a duty to grant the same rights to others, but more consequentially, rights have trade-offs: things we have to do or surrender in order to earn the right. The right to vote entails the duty to pay taxes. The right of free speech entails the duty of using it responsibly, not inciting violence, harm, insurrection.

So it is with rights in our information age. Every cyber right entails a cyber duty.

For example, security. Modern security is an attribute of systems. Your thing, your home, your company, cannot maintain security alone outside of a system. Once a digital device is connected, everything it connects with needs to be secure as well. In fact, any system will only be as secure as the weakest part of that system. If your part is 99% secure, but your colleague is only 90% secure, you are actually only 90% secure as well. This small difference is huge in security. There are documented cases where an insecure baby monitor in a household system became the back door to unauthorized entry into that family’s network. In this way, the lax security of one piece sets the security for the whole system

Therefore, every part of a system has a duty to maintain the required level of security. Since one part’s security in part determines and impacts all parts’ security, every part of the system can rightfully demand that all parts level up. It is therefore the duty of each part (person, organization) to maintain the proper security. It is not hard to imagine protocols that say you and your devices can’t join this network unless you can demonstrate you have proper security. In short you have the right to connect to the public commons (without permission), but you have the duty to ensure the security of your connection (and the commons as a whole).

This is not much different from what most nations say, which is you have a right to use any public road, but you must demonstrate you are responsible for its safety and security by passing a driver’s test. Your right is mobility on the roads; your duty is drive responsibility (no drinking!), and to get a license to prove it.

There are other rights/duties animated by digital tech, such as your identity. You don’t really need a name yourself. Your name is most useful to other people, so they can identify you, and in turn, trust you. Like your face, your name is at once the most personal thing about you and the most public thing about you. Your name and face are both indisputably “yours” and also indisputably in the commonwealth. Our faces are so peculiarly public that we are spooked about people who hide their face. And legally, many activities require that we keep our face public, like getting a license, flying in a plane, entering a secure facility, or voting. We have a right to look however we like, but we also have an obligation to keep our face public.

Names are similar, both intensely personal and outright public. We can try to hide our names behind pseudonyms and anonymity, but that diminishes some of our powers to affect change in the world, and also reduces trust from others. Privacy is part of a tradeoff. In order to be treated as an individual, with respect, we have to be transparent as an individual. We have a history, we have a story, we have context, we have needs and talents. All this is wrapped in our identity. So in order to be treated as an individual we have to convey that identity. Personalized individuality is a right that demands a duty of transmitting our identity. We also have (and must have) the right to remain opaque, unknown, and hidden, but the tradeoff for that right is the duty to accept that we will be treated generically, as not-an-individual, but as a number. The right of obscurity is the duty of silence; the right of individuality is the duty of transparency.

As more of our lives are connected constantly, the distinction between digital rights and rights in the rest of the world tend to vanish. I don’t find it useful to separate them. However, there will still be new “rights” and “responsibilities” arising from new technology. They will first appear in high tech, and then as that tech becomes the norm, so will the rights. Currently, generative AIs demand we think about the rights – and responsibilities – of referencing a creation. The right of copy, or copyright, addressed the need to govern copies of a creation. Generative AI does not make copies, so copyright norms are helpless with this. We realize now that there might be the need for articulating a new right/duty around training an intelligence. If my creation is referenced to be used to train a student, or train an AI, that is, an agent that will go to create things themselves influenced by my work, should I not receive something for that? Should I have any control over what is made from my influence? I can imagine an emerging system such that any creation that is granted copyright is duty bound to be available for reference training by others, with the corresponding right for anyone to train upon a creation with a duty to pass some of the credit (status and monetary) back to creators.

The mirroworlds of AR and XR will necessitate further new pairs of rights/responsibilities around the messy concerns of common and shared works, for the mirrorworld is 100% a commons. What do I get from a collaborative creation, and what do I owe the others who contribute, when those boundaries are unclear? Because every new technology generates new possibilities, I expect it to also produce new pairs of duties and rights.

Weekly Links, 02/16/2024

- Google’s secret superpower in AI will not be faster, cheaper, smarter models. It is YouTube. Once they train their models on the billions of YouTubes, they will open up a whole new platform. Multimodal prompting with a 44-minute movie | Gemini 1.5 Pro Demo

- A Digital AND Analog clock: Digital +Analog clock ⏰ ⌚️

The Scarcity of the Long-Term

The chief hurdle in constructing a Death Star is not the energy, materials, or even knowledge needed. It’s the long time needed. A society can change their mind mid-way over centuries, and simply move on. The galaxy is likely strewn with abandoned Half-a-Death Stars.

Despite the acceleration of technological progress, indeed because of it, one of the few scarcities in the future will be a long attention span. There will be no shortage of amazing materials that can do magic, astounding sources of energy to make anything happen, and great reserves of knowledge and know-how to accomplish our dreams. But the gating factor for actually completing those big dreams may be the distractions that any society feels over the centuries. What your parents and grandparents found important you may find silly, or even embarrassing.

To build something that extends over multiples of individual lifespans requires a very good mechanism to transmit the priority of that mission. It is much easier to build a rocket that will sail 500 years to the nearest star, then it is to ensure that the future generations of people born on board that 500-year rocket maintain the mission. It is very likely that before it reaches the 250-year halfway point, that the people on board turn it around and head back to a certain future. They did not sign up for this crazy idea!

It is certain that 250 years after the launch of that starship, the society that made it will have wonderous new technologies, new ideas, maybe even new ways to explore, and they could easily change their mind about the importance of sending flesh into space, or decide to explore other frontiers. That is not even to mention how the minds of those onboard could also be changed by new inventions in 250 years.

If let alone, an advanced civilization, could over many millennia, invent AIs and other tools that would allow it to invent almost any material it could imagine. There would be no resource in the universe it could not synthesize at home. In that sense, there would be no material and energy scarcity. Perhaps no knowledge scarcity either. The only real scarcity would be of a long attention span. That is not something you can buy, or download. You’d need some new tools for transmitting values and missions into the future.

There’s an ethical dilemma around transmitting a mission into the far future. We don’t necessarily want to burden a future generation with obligations they had no choice in; we don’t want to rob them of their free will to choose their own destinations. We DO want to transmit them opportunities and tools, but it is very hard to predict which are the gifts and which are the burdens from far away. There’s a high probability, they could come regard our best intentions as misguided, and choose a very different path, leaving our mission behind.

In this way it is easy to break the chain of a long-term mission. one that is far longer than an individual lifespan, and perhaps even one that is longer than a society life-span. It may turn out that the most common scarcity among galactic advanced civilizations is a long-term attention span. Perhaps vanishing few ever complete a project that lasts as long as a 1,000 years. Perhaps few projects remain viable after 500 years.

I am asking myself, what would I need to hear and get from a past generation to convince me to complete a project they began?

Hill-Making vs Hill-Climbing

There are two modes of learning, two paths to improvement. One is to relentlessly, deliberately improve what you can do already, by trying to perfect your process. Focus on optimizing what works. The other way is to create new areas that can be exploited and perfected. Explore regions that are suboptimal with a hope you can make them work – and sometimes they will – giving you new territory to work in. Most attempts to get better are a mix of these methods, but in their extremes these two functions – exploit and explore – operate in different ways, and require different strategies.

The first mode, exploiting and perfecting, rewards efficiency and optimization. It has diminishing returns, becoming more difficult as fitness and perfection is increased. But it is reliable and low risk. The second mode, exploring and creating, on the other hand, is highly uncertain, with high risks, yet there is less competition in this mode and the yields by this approach are, in theory, unlimited.

This trade off between exploiting and exploring is present in all domains, from the personal to the biggest systems. Balancing the desire to improve your own skills versus being less productive while you learn new skills is one example at the personal level. The tradeoff between investing heavily in optimizing your production methods instead of investing in new technology that will obsolete your current methods is an example of that tradeoff at the systems level. This particular tradeoff in the corporate world is sometimes called the “innovator’s dilemma.” The more efficient and excellent a company becomes, the less it can afford to dabble in some new-fangled idea that is very likely to waste investments that can more profitably be used to maximize their strengths. Since statistically most new inventions will fail, and most experiments will not pan out, this reluctance for the unknown is valid.

More importantly, if new methods do succeed, they will cannibalize the currently optimal products and processes. This dilemma makes it very hard to invest and explore new products, when it is far safer, more profitable, to optimize what already works. Toyota has spent many decades optimizing small efficient gasoline combustion engines; no one in the world is better. They are at the peak of gas car engines. Any money spent on investing into unproven alternative engines, such as electric motors, would reduce their profits. They would be devolving their expertise and becoming less excellent. They cannot afford to be less profitable.

Successful artists, musicians and other creatives have a similar dilemma. Their fans want more of what they did to reach their success. They want them to play their old songs, paint the same style paintings, and make the same kind of great movies. But in order to keep improving, to maintain their reputation as someone creative, the artists need to try new stuff, which means they will make stuff that fails, that is almost crap, that is not excellent. To win future fans the artist has to explore rather than merely exploit. They have to take up a new instrument, or develop a new style, or invent new characters, which is risky. Sequels are just so much more profitable.

But even sequels – if they are to be perfect – are not easy. They take a kind of creativity to perfect. This kind of everyday creativity, the kind of problem solving that any decent art or innovation requires, is what we might call “lower-case” or base creativity. Devising a new logo, if done well, requires creativity. But designing logos is a well-trod domain, with hundreds of thousands of examples, with base creativity as the main ingredient. Designing another great book cover is primarily a matter of exploiting known processes and skills. Occasionally someone will step up and create a book cover so unusual and weird but cool that it creates a whole new way to make covers in the future. This is upper-case, disruptive Creativity.

Upper-case, disruptive Creativity discovers or creates new areas to be creative in. It alters the landscape. Most everyday base creativity is filling in the landscape rather than birthing it. Disruptive Creativity is like the discovery of DNA, or the invention of photography, or Impressionism in art. Rather than just solving for the best possibility, it is enlarging the space of all possibilities.

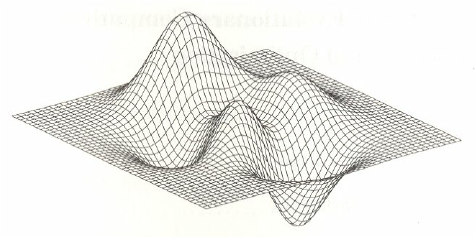

Both biologists and computer scientists use the same analogy when visualizing this inherent trade-off between optimization and exploration. Imagine a geological landscape with mountains and valleys. The elevation of a place on the landscape is reckoned as its fitness, or its technical perfection. The higher up, the more fit. If an organism, or a product, or an answer is as perfect as it can be, then it registers as being at the very peak of a mountain, because it cannot be any more fit or perfect for its environment. Evolution is pictured as the journey of an organism in this conceptual landscape. Over time, as the organism’s form adapts more and more to its environment, this change is represented as that organism going up (getting better), as it climbs toward a peak. In shorthand, the organism is said to be hill-climbing.

Computer scientists employ the same analog to illustrate how an algorithm can produce the best answer. If higher up in the landscape represents better answers then every slope has a gradient. If your program always rewards any answer higher up the gradient, then over time it will climb the hill, eventually reaching the optimal peak. The idea is that you don’t really have to know what direction to go, as long as you keep moving up. Computer science is filled with shortcuts and all kinds of tricks to speed up this hill-climbing.

In the broadest sense, most every-day creativity, ordinary innovation, and even biological adaptation in evolution is hill climbing. Most new things, new ideas, most improvements are incremental advances, and for most of the time, this optimization is exactly what is needed.

But every now and then an upper-case, disruptive jump occurs, creating a whole new genre, a new territory, or a new way to improve. Instead of incrementally climbing up the gradient, this change is creating a whole new hill to climb. This process is known as hill-making rather than hill climbing.

Hill-making is much harder to do, but far more productive. The difficulty stems from the challenge of finding a territory that is different, yet plausible, inhabitable, coherent, rather than just different and chaotic, untenable, or random nonsense. It is very easy to make drastic change, but most drastic changes do not work. Hill-making entails occupying (or finding*) an area where your work increases the possibilities for more work.

If a musician invents a new instrument, rather than just another song, that new instrument opens up a whole new area to write many new songs in, new ways to make music that could be exploited and explored by many. Inventing the technology of cameras was more than merely an incremental step in optics, it opened up vast realms of visual possibilities, each of those, such as cinema, or photojournalism, became new hills that can be climbed. The first comedians to figure out stand-up comedy, created a whole new hill – a new vocation that could be perfected.

The techniques needed for this upper-case Creativity, this disruptive innovation, this hill-making, are significantly different from the techniques for hill-climbing. To date, generative LLM-AI is capable of generating lower-case base creativity. It can create novel images, novel text, novel solutions that are predominately incremental. These products may not be things we’ve seen or heard before, or even things we would have thought of ourselves, but on average the LLMs do not seem to be creating entirely new ways to approach text, images, and tasks. So far they seem to like the skill of making a new hill.

Hill-making demands huge inefficiencies. There is a lot of wandering around, exploring, with plenty of dead ends, detours, and dry deserts where things die. The cost of exploring is that you only discover something worthwhile occasionally. This is why the kinds of paths that tend toward hill-making such as science, entrepreneurship, art, and frontier exploration are inherently expensive. Most of the time nothing radically new is discovered. Not only is patience needed, but hill-making requires a high tolerance of failure. Wastage is the norm.

At the same time, hill-finding requires the ability to look way beyond current success, current fitness, current peaks. Hill-finding cannot be focused on “going up the gradient” – becoming excellent. In fact it requires going down the gradient, becoming less excellent, and in a certain sense, devolving. The kind of agents that are good at evolving towards excellence are usually horrible in devolving toward possible death. But the only way to reach a new hill – a hill that might potentially grow to be taller than the hill you are currently climbing – is to head down. That is extremely hard for any ambitious, hard working person, organism, organization, or AI.

At the moment generative AI is not good at this. At the moment AI and robots are very good at being efficient, answering questions, and going up gradients towards betterment, but not very good at following hunches, asking questions, and wondering. If, when, they do that, that will be good. My hope it that they will help us humans hill-find better.