|

Start with Technology, End with Trust

The central economic imperative of the industrial age was to

increase productivity. Every aspect of an industrial firm—from its

machines to its organizational structure—was tailored to enhance

the efficiency of economic production. But today productivity is a

nearly meaningless byproduct in the network economy.

The central economic imperative of the network economy is

to amplify relationships.

Every aspect of a networked firm—from its hardware to

its distributed organization—is created to increase the quantity

and quality of economic relationships.

The network is a structure to generate relationships.

Networks haul relations the way rivers once hauled freight. When

everything is connected to everything else, relationships are rampant.

Each variety of connection in a network begets a relationship. Between

firms and other firms. Between firms and customers. Between customers

and the government. Between customers and other customers. Between

employees and other firm’s employees. Between customers and

machines. Between machines and machines, objects and objects, objects

and customers. There is no end to the complexity and subtlety of

relationships spawned in a network economy.

Each of these types of relationship has its own specific

dynamics and quirks. And each is nurtured by a particular type of

technology. The technologies of jelly bean chip and boundless bandwidth

are, in the end, relationship technologies. "We need to shift away

from the notion of technology managing information and toward the idea

of technology as a medium of relationships," writes Michael Schrage

in Shared Minds, a book about the new technologies of

collaboration. Despite the billions of bits that information hardware

can process in a second, the only matter of consequence silicon produces

are relationships.

Of course reputation and trust have been essential in all

economies of the past, so what’s new? Only two things:

- With the decreased importance of productivity,

relationships and their allies become the main economic event.

- Telecommunications and globalism are intensifying,

increasing, and transforming the ordinary state of relationships into an

excited state of hyperrelations—over long distances, all the time,

all places, all ways. It’s not Kansas anymore; it’s Oz.

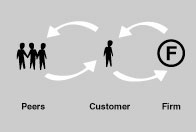

Relationships among more than two people can be structured as

hierarchies or as networks. In hierarchies, members are ranked in

privilege relative to one another; in networks, members relate as

peers—counterparts of similar power and opportunity. In previous

ages the most intelligent way to construct a complex organization in the

absence of plentiful information was to build a hierarchy. Rank is a

clever and workable substitute for ubiquitous real-time information.

When information is scarce, follow orders.

When information is plentiful, peers take over.

In fact, as reliable information becomes common, almost

nothing can stop peers from taking over. As computers and communications

unloose a million bits of information in every dimension, we see

peerages form in every dimension. Email and voice mail have brought

peerage pressure to corporations. The flattening effect of network

technologies and the subsequent turmoil in the organization of business

firms is well recognized. But in many ways the emerging peerlike

relationship between boss and staff is probably the least interesting

and least important of all the relational changes now taking place.

More consequential is the relation between customer and firm,

which is yielding to the peer effect. More important still is the

relation between firm and firm, which is shifting rapidly to a web of

overlapping nets. Still more vital is the lateral relation between

customer and customer, which is just beginning to brew. Finally, the

elevated relation between customers (rather than citizens) and the rest

of society, a relation that is just now being defined, may be the most

important of all, as economics elbows its way into every activity. As an

example of expanding relationships, consider the traditional

relationship between customer and a firm, roles that have been around

forever. In the network economy the separation between customers and a

firm’s employees often vanishes.

When you pump your own gas at the filling station, are you

working for the gas station or for yourself? Are all those people

waiting in line behind the ATM machine more highly evolved bank

customers or just nonpaid bank tellers? When you take a pregnancy test

at home, are you a savvy self-helper, or part of the HMO’s plan to

reduce costs? The answer, of course, is both. When everyone is linked

into a web, it’s impossible to tell which side you are on.

Web sites and 800 numbers can invite customers into the

internal knowledge banks of a company to almost the same degree of

"inside" that employees stationed on the other side of the

line enjoy. Many technical companies post the same technical information

and diagnostic guidelines on their help sites that their own support

professionals work from when you call their hotline. You can have

someone trained to look up and then read troubleshooting answers for

you, or if you are in a hurry, you can try to find it yourself.

Who’s working for whom?

At the same time the complexity of an employee contract,

particularly in high-tech fields, is quickly approaching the complexity

of a contract with an outside vendor. Stock options, vestment periods, a

thousand insurance and benefit combinations, severance clauses,

noncompete agreements, performance goals—each one uniquely

negotiated for each person. A highly paid technical employee becomes in

essence a permanent consultant. He or she is an outsider on staff.

Outsiders act as employees, employees act as outsiders.

New relationships blur the roles of employees and customers to the point

of unity. They reveal the customer and company as one.

This close coevolution between users and producers is more

than poetry. There is a very real sense in which the owners of the phone

network sell nothing at all but the opportunity for customers to have

conversations among themselves—conversations which the users

themselves create. You could say the phone companies cocreate phone

service. This blurring between origin and end spills over into the birth

of online services, such as AOL, where most of what is now sold is being

created by the customers themselves in the form of postings and chat. It

took years for AOL to figure this out; they initially wanted to follow

industrial logic and sell downloadable information created at great

expense by professionals. But once they realized that the customers

acted like employees by making the goods themselves, the online

companies started making money.

The net continues to break down the old relationships between

producers of goods and consumers of services. Now, producers consume and

consumers produce.

In the network economy, producing and consuming fuse into

a single verb: prosuming.

"Prosumer" is a term coined by Alvin Toffler in

1970 in his still-prescient book Future Shock. (Toffler first

found his insights as afuturist while working for the telephone

networks.) Today prosumers are everywhere, from restaurants where

you assemble your own dinner, to medical self-care arenas, where you

serve as doctor and patient.

The future of prosumerism can be seen most clearly online,

where some of the very best stuff is produced by the people who consume

it. In a multiplayer game like Ultima Online, you get a world with a

view and some tools and then you’re on your own to make it

exciting. You invent your own character, develop his or her clothing or

uniform, acquire unique powers, and build the surrounding history. All

the other thousands of characters you interact with have to be sculpted

by other prosumers. The adventures that unfurl are cocreated entirely by

the participants. Like a real small town, the joint

experience—which is all that is being sold—is produced by

those who experience it.

These eager world makers could be viewed as nonpaid content

makers; in fact, they will pay you to let them make things. But the same

world could also be viewed as full of customers who have been given

tools with which they can complete a product to their own picky

specifications. They are rolling their own, just as they like. In the

new economy-speak, this is known as mass customization.

The premise of mass customization is simple. Technology

allows us to target the specifications of a product to a smaller and

smaller group of people. First we can make Barbie dolls in the millions.

Then with more flexible machinery and computer-generated target

marketing we can make ethnic Barbies, in the hundreds of thousands. Then

with improved market research and advanced communications we can make

subculture Barbies, biker and grunge Barbies in the thousands.

Eventually, with the right network technology, we can make the personal

Barbie, the Barbie of you. In fact there is a company in Littleton,

Colorado, that currently makes the "My Twinn" baby doll to

look like the doll’s owner. The doll’s eye and hair color and

hair style are matched to a photo of the child who will own it.

The most interesting aspect of prosuming and mass

customization—of this new relationship between the customer and the

firm—is that because customers have a hand in the creation of the

product they are more likely to be satisfied with the final result. They

have taught the firm how to please them, and the firm now has a customer

with a much fuller relationship with them than before.

But creating a product for "a niche of one" is only

a small part of the transformation of the customer relationship.

(Detroit car makers learned long ago to create customized cars, but that

was all they learned.) Network technologies such as data mining, smart

cards, and recommendation engines are escalating the levels of

relationships available to customers.

The drive to relate to the consumer intimately, to the point

of encouraging prosuming, can be articulated as a series of progressive

goals:

1) to create what the customer wants

2) to remember what the customer wants

3) to anticipate what the customer wants

4) finally, to change what the customer wants

Each of the missions elevates the firm’s commitment to

the customer and raises the customer’s involvement with the

firm.

To create what the customer wants. Sometimes this will

mean simple customization: You want a vacation experience unlike anyone

else’s. Sometimes this will mean mass customization: You want a

pair of jeans that fit your unusual leg shape at the same price as a

regular pair of jeans. Sometimes mass customization is not what you

want. The huge fashion industry makes its fortune on people’s

dependable desire for wearing what everyone else is wearing. Sometimes

what you want is semicustomized: You read the New York Times because

everyone else is reading it, but you don’t read the sports section

or the obits. You want not the Daily Me, but the Daily You and Me, the

publication your 12 closest friends read.

A huge tide of information and trust must flow between users

and creators in order to create exactly what the customer wants. The

interface technology must be clear and simple for people to convey their

desires. The nightmarish logistics of delivery and production must be

managed with exactness. The most difficult aspect of this mission may

not be the order form but the manufacturing; anything that involves

atoms is much harder to customize than first thought. But any solutions

surely involve networked technologies.

To remember what a customer wants. A majority of the

things we do, we do repetitively. We engage in the same tasks every day,

or once a week, or every now and then. Things done iteratively have

different dynamics from things done once. Little events become

important. We bristle at having to remember our password again, or

having to recite how we like our coffee one more time, or having to

explain again what we don’t like about bathing suits. Humans who

learn our quirks (and they must be learned) earn our favor. Firms who

learn our quirks will also earn our favor.

The technology of tracking and interpreting our whims

heightens the relationships between firm and consumer. The firm must

expend great effort to remember your preferences, but you also expend

effort in teaching them so they can remember. And the remembering must

be intelligent. You order the same espresso every day, except when

it’s cold out, and then you order a latte. The relationship tech

has to be robust enough to be taught these distinctions.

Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, authors of the amazingly

insightful Enterprise One to One, state: "A Learning

Relationship between a customer and an enterprise gets smarter and

smarter with every individual interaction, defining in ever more detail

the customer’s own individual needs and tastes. Every time a

customer orders her groceries by calling up last week’s list and

updating it, for instance, she is in effect ‘teaching’ the

service more about the products she buys and the rate at which she

consumes them." In reward for the firm’s effort at being

taught, the firm and the customer develop a committed relationship.

Peppers and Rogers continue: "The shopping service will develop a

knowledge of this particular customer that is virtually impossible for a

competitive shopping service to duplicate, providing an impregnable lock

on the customer’s loyalty." At the same time, the customer has

invested so much in the relationship that the cost of switching to

another vendor gets steeper by the day. Peppers and Rogers: "When

the florist sends a note reminding you of your mother’s birthday,

and offers to deliver flowers again this year to the same address and

charged against the same credit card you used with the florist last

year, what are the chances that you will pick up the phone and try to

find a cheaper florist?"

Since a relationship involves two members investing in it,

its value increases twice as fast as one’s investment.

The cost of switching relationships is high. Leaving, you

surrender twice. You give up all that the other has put into the

relationship, and you give up your own investment. In other words, the

cost of loyalty is low. Thus we see the huge success of frequent flyer

and frequent buyer programs, made possible by the coinvestment that

airlines and supermarkets put into them. Affiliation cards are another

example of the relationship extension; the costs of tracking purchases

are so low compared to the value of belonging—for both

sides—that it pays to invent other ways to spread the idea. And the

phone companies’ attempts at "friends of friends" calling

circles are likewise clever experiments in exploiting networked

relationships.

Smarter relationship technology, or "R-tech" as

economist Albert Bressand calls it, will bind the connections between

customers and firms more tightly still. An emerging standard called P3P

offers a uniform way to store an individual’s profile containing

name, address, and so forth as well as preferences, including

preferences of what they will reveal. If you shop a lot you will carry a

"passport profile" based on the P3P protocol (or one similar)

encased in your smart card or online in a browser. You exchange it with

the vendor during a commercial transaction. The passport technology will

help firms remember you as you teach them how to serve you and earn your

favor.

The portability of preferences is a big deal. As the net

creeps into yet more aspects of commerce, the ability to track

identities and desires across different systems will be key. The

Ritz-Carlton Hotel is justifiably proud of its ability to customize

rooms for you anywhere in its thirty-one-hotel chain, without having to

ask you. Some airlines can do the same. That still leaves a lot of room

for success in creating relationships in the network economy as a

whole.

To anticipate what a customer wants. Creating

tailored products for people is the first step of R-tech. The second is

recalling their preferences intelligently. The third step is

anticipating what they’ll want even before they articulate it.

That’s a measure of any great relationship. You can boast you

really know someone when you can say, "I know she’ll love this

book!"

The most elemental form of anticipatory tech extrapolates

likes and dislikes from the customer’s past usage patterns. But the

most powerful forms of R-tech rely on the swarm of other customers and

the latent relationships between them to anticipate desires. A great

example of this social R-tech was developed by Firefly, a web-based

recommendation engine (recently sold to Microsoft). Here’s how it

works in brief: I tell MyLaunch, Firefly’s music vendor, my ten

favorite music albums. It takes my recommendations and compares them

with the top ten recommendations of 500,000 other Firefly members

interested in music. Firefly then figures out where in "taste

space" I belong. It places me near the few people who like the same

albums I do. Despite an overlap of taste with them there will be a few

albums my neighbors mentioned that I did not. Firefly will alert me to

those albums, and conversely will tell my taste neighbors about the

albums I mentioned that they had not. These are the albums I should try

because it anticipates I will like them.

It’s remarkable how well this simple system works. I

eerily recommended great albums that I liked. There are many refinements

to increase its power. I can "teach" the system by grading the

results it gave me. Perhaps it recommended Pete Seeger because I named

Bob Dylan as a favorite. But say I happen to already know Seeger’s

work and can’t stand him, so I tell it to forget Seeger (and thus

Seeger-likes). It’s now smarter. I can further locate my space with

more precision by rating as many albums as I wish, indicating my love or

hate of them. (A strong negative rating is just as useful as a strong

positive rating.) Because it is the web, I also have the option of

listening to music selections to refresh my memory or evaluate

recommended candidates.

|

People who share small preferences for particular books or movies in a

single "taste space" can use thier collaborative sorting to

aid them in future purchases.

|

The real power of this system lies not in mere

recommendation, but in its ability to create relationships among its 3

million registered users. It allows members to link up with their

taste-neighbors. All the fans of ambient music, or early Seattle grunge,

are encouraged to strike up conversations in "venues," or

start mail lists, or simply introduce themselves. Out of this technology

is born yet another relationship: self-identity.

Most listeners don’t have easily classifiable tastes.

They’re fans of Nirvana, U2, The Beatles, Joni Mitchell, and Nine

Inch Nails. They’ll have neighbors in an obscure unnamed

space—the Beatles/U2/NineInchNails space. Through Firefly, these

folks can identify their tastes by the microcommunity of like-minded

folks they create for themselves. What Firefly can do with music, it can

also do with books. And movies. And web pages. (Firefly recently spun

each of these domains out to separate partners.) They are rated in the

same way, with equally useful results. But now the combined media space

is tremendously potent. Weird subcultures can be detected long before

they have a name. Readers of Anne Rice vampire novels who like country

and western music and Woody Allen movies suddenly realize they are a

group! Self-recognition is the first step toward influence.

Online booksellers such as Amazon.com and Barnes and Noble

are using similar R-technology to sell more books, and to make customers

smarter shoppers. Amazon derives its collaborative recommendations from

customers who have a purchasing behavior similar to yours. Based on what

you have bought in the past, and what others have bought in the past,

Amazon advises: Dear reader, you should like these titles. And, they are

usually right. In fact, their recommendations are so handy that they are

Amazon’s prime marketing mechanism and their chief source of

revenue growth. According to company spokespersons,

"significant" numbers of users buy additional books—on

impulse—because of the co-recommendations that pop up when you

inspect a book.

Evan Schwartz, author of Webonomics, goes so far as to

suggest that firms such as Amazon should be viewed as primarily selling

intangible relationships. "Amazon should not be compared to actual

stores selling books. Rather . . . the value that Amazon adds is in the

reviews, the recommendations, the advice, the information about new and

upcoming releases, the user interface, the community interest around

certain subjects. Yes, Amazon will arrange to deliver the book to your

door, but you as a customer are really paying them for the information

that led to your purchase." When you log on to Amazon you get a

relationship generator, one that increasingly knows you better.

The beauty of network logic is that the mechanics of this

software does not rely on artificial intelligence, or AI. Rather the

collaborative work is done by pooling the teaching that each person

would do alone into one distributed base. It’s an example of dumb

power. Lots of people teaching a dumb program, but all connected

together, producing useful intelligence. The strength of the network is

built by the slim bits of information that each member is willing to

share. Sometimes that’s all it takes.

The web is a hotbed of innovations in R-tech. If you had

success in a search and are willing for that information to be spread

collectively to others, this lateral relationship can improve the search

function for everyone. Sometimes called "collaborative

filtering" these kinds of social network functions will spread

widely within the web itself, as well as within companies and small work

groups.

As in other technological evolutions, relationship tech

will begin its innovation in the avant garde, then work back to the

familiar.

R-tech first appears in the world of the web, but will

gradually infiltrate the world of canned goods and sports equipment, as

well as TV shows and vacation spots. Eventually it reaches the final

stage in the progression of customer relations:

To change what a customer wants. The

ongoing tango between customer and provider draws them together until

their identities disappear at times. This is especially true in frontier

arenas, where expertise is usually in short supply. At first there is no

authority on what customers want or what providers should

deliver—as in these early days of the web and e-commerce. Expertise

has to be developed jointly, coevolved. Customers must be trained and

educated by the company to teach them what they need, and then the

company is trained and educated by the customers. We saw precisely this

equation in the pioneer days of online conferencing about a decade ago.

When email and chat began, no one knew the difference between great

email and okay email, between fabulous chat areas and average chat

areas. The best online companies learned all they knew from their first

customers. But the customers, too, had little expertise of what to

expect and so relied on the visions and vaporware suggested by the

companies. Customer and company educated each other on what was

possible.

Good products and services are cocreated: The desires of

customers grow out of what is possible, and what is possible is made

real by companies following new customer desires. Because creation in a

network is a cocreation, a prosumptive act, a multifaceted relationship

must exist between the cocreators.

Cocreation and prosumption require an information peerage.

Information must flow symmetrically to all nodes. In the industrial

society, the balance of information inevitably sided with corporations.

They had centralized knowledge while the customer had only their own

solo experience divorced from that of all but a few friends. The coming

network economy has changed that. Each new layer of complexity and

technology shifts the action toward the individual.

The intent of networked technology is to make the customer

smarter. This may require sharing previously proprietary knowledge with

the customer. It may also be as simple as sharing what the company knows

about the customer with the customer herself.

R-tech tries to rebalance the traditional asymmetrical flow

of information, so that the customer learns as fast as the firm (and so

the firm learns as fast as the customer). At first the idea of focusing

on "learning customers" instead of the "learning

company" seems misplaced. But it is part of the larger shift away

from a view of the firm as a standalone unit and toward a view of the

firm as an interacting node in a much larger network—a diffuse node

made up of customers as well as employees.

Letting the customer learn with help from the firm is not the

only way to make the customer smarter. The other way is to reverse the

usual flow of information in the market. John Hagel, co-author of Net

Gain, says, "Instead of helping your firm capture as much

information about the customer as you can, you want the customer to

capture as much information about themselves as they can." And you

want customers to capture as much information about the firms they are

dealing with as well. There are several ways on the web to bias

information toward the customer. Among the most exciting innovations are

new vendors that send a bot around to comparison shop for you. If thirty

music retailers online offer the soundtrack to the movie Titanic

for sale, web sites such as Junglee or Jango will collect the offers

from each vendor, and rank them for you. But the vendors are calling the

shots; they craft the offer, keep the data of requests, and drive the

sale.

By reversing the direction of information flow one can create

a "reverse market." In a reverse market (already set by a few

web sites), the customer dictates the terms of sale. You say,

"I’d like to buy a Titanic CD for $10, new." You

broadcast your offer into the web, and then the vendors come to you.

This works best at first for high-ticket items such as cars, insurance,

and mortgages. "I’d like a $120,000 thirty-year mortgage for

my house in San Jose. I can pay $1,000 per month. Do I have any

takers?" You set the terms, keep the data, and drive the

transaction. Technology, of course, means that much of this negotiation

happens in the background via agents and so forth; you don’t have

to do the haggling yourself. But the R-shift moves the capture of

information into the hands of customers from those of the vendors. It

makes the customer smarter.

And whoever has the smartest customers wins.

The third way to make the customer smarter is by connecting

customers into a collective intelligence.

When personal computers first entered the marketplace in the

mid 1970s, user groups sprung up everywhere to assist the perplexed.

Anyone could attend a monthly meeting and swap useful tips about how to

set up a printer, or get an upgrade program to work. It was all

informal, and free, and democratic; those who knew, told; those who

didn’t know, asked questions and took notes. Each specific computer

platform spawned local user groups in major cities. There were user

groups for "orphan" equipment such as Amigas, and video game

consoles, and of course for Macs and DOS-based PCs. Some user groups

grew to have tens of thousands of members and some ran their own free

software emporiums and had budgets in the millions of dollars.

|

Firms that encourage customers to talk to each other, to form affinity

groups and hobby tribes, will breed smarter and more loyal customers

while creating smarter products and services.

|

User groups were seen by the outside world as evidence of the

lousy state of the computer industry. Manuals were horrible, interfaces

unfriendly. Critics complained that you didn’t need to join a user

group to get your TV up and running, or to turn your dishwasher on. Yet

for many computer wannabees, the shared knowledge of a user group was

essential in starting the journey into computerdom, or later onto the

net and the web.

In reality, user groups were not a sign of failure but a sign

of intelligence. They were a means of making the consumer smarter. Some

computer companies caught on to this reality early and made regular

visits to the bigger user groups to answer questions and hear complaints

and pick up suggestions. The user group, although independent and

nonprofit, became part of the computer companies’ extended

self.

Today there are still some 2,000 Mac and PC user groups that

offer regular meetings in the United States (and an equal number

internationally). The Berkeley Mac User Group still boasts 10,000

members, and weekly meetings. Yet most user group action has

shifted to the online space. Web sites with attendant conversation

areas, FAQ (Frequently Asked Questions) archives, mail lists, and public

bulletin boards all keep the distributed exchange of knowledge

going.

A user group is a peerage of responsibility. Group members

take education into their own hands, and distribute the job of keeping

up among themselves. It’s long been appreciated that the best and

most useful working knowledge about technical gear comes out of user

groups. User groups are now a regular feature for avocations such as

scuba diving, bicycling, saltwater aquariums, hot-rod cars, or any hobby

where technological change seems to outrun understanding.

The most fanatical of user groups can be thought of as

"hobby tribes," a phrase coined by science fiction writer

David Brin. Hobby tribes are very informed, very connected, very smart

customers. They band their enthusiasms together and become the experts.

In some smaller niches they become the market, too.

Expertise now resides in fanatical customers. The

world’s best experts on your product or service don’t work for

your company. They are your customers, or a hobby tribe.

Companies need user groups almost as much as users need them.

User groups are better than advertising when customers are happy, and

worse than cancer when they are not. Used properly, aficionados can make

or break products.

The network economy has the potential to enable a

civilization of aficionados. As customers get smarter, the locus of

expertise shifts toward affiliates and home-brew groups, and away from

large corporations or the solo academic professional. If you really want

to know what works, or where to find it, ask a hobby tribe. And not just

in the realm of high-tech knowledge. All knowledge is pooling into

aficionados. Because of shared obsessions among horse lovers, there are

more horseshoers working today than a hundred years ago, in the age of

cowboys. There are more blacksmiths making swords and chain mail armor

this year than ever worked in the medieval past. A network of

aficionados is already here.

The net tends to dismantle authority and shift its allegiance

to peer groups. The cultural life in a network economy will not emanate

from academia, or the cubicle of corporations, or even primetime media.

Rather, it will reside in the small communities of interest known as

fans, and ’zines, and subcultures. In Future Shock Alvin

Toffler setsthe stage: "Like a bullet smashing into a pane of

glass, industrialism shatters societies, splitting them up into

thousands of specialized agencies . . . each subdivided into smaller and

still more specialized subunits. A host of subcults spring up; rodeo

riders, Black Muslims, motorcyclists, skinheads, and all the rest."

That initial shatter is now several thousands of subcultures. For every

obsession in the world, there is now a web site. What industrialization

began by shattering, the network economy completes by weaving together

and serving with great attention. The web of broken shards is now the

big picture.

Information shifts toward the peerage of customers, so

does responsibility for success. The net demands wiser customers.

The advent of relationship technologies on the net creates a

larger role for the customer, and it puts more demands on the consumer,

too. None of this enlargement of relationships can happen unless there

are vast amounts of trust all around. "The new economy begins with

technology and ends with trust," says Alan Weber, founder of the

new economy business magazine Fast Company.

If you send all your workers home to telecommute, you’ll

need a whopping lot of trust between you and your workers for that

relocation to succeed. If I tell Firefly all the books I read, all the

movies I watch, and all the web sites I visit, I will require a high

degree of trust from them. If Compaq lets me delve into its expensively

compiled knowledge database of known bugs and problems with certain

computer parts, it has to trust me.

Trust is a peculiar quality. It can’t be bought. It

can’t be downloaded. It can’t be instant—a startling fact

in an instant culture. It can only accumulate very slowly, over multiple

iterations. But it can disappear in a blink. Alan Weber compares its

accretion to a conversation: "The most important work in the new

economy is creating conversations. Good conversations are about

identity. They reveal who we are to others. And for that reason, they

depend on bedrock human qualities: authenticity, character, integrity.

In the end, conversation comes down to trust."

A conversation is a pretty good model for understanding what

is going on in the network economy. Some conversations are short, abrupt

exchanges of minimal data; some are antagonistic, some are periodic,

some are continuous, some are long-distance, some are face to face. A

back-and-forth exchange starts between two people, and then spills over

to several people, and as the conversation becomes multipronged and

divergent, it gathers in more and more players. Eventually there are

conversations between firms and objects as well as people, as more of

the world’s inanimate artifacts become connected. Increased

animation increases the number or times of interaction, and the

frequency of conversation. The more interactions, the more important

learning becomes, the more essential relationships become, the more

trust becomes a factor. Trust becomes what Weber calls "a business

imperative."

But for all the talk of the importance of trust, it only

comes at a price. It comes slow and it always comes awkwardly.

"Trust can be messy, painful, difficult to achieve, and easy to

violate," writes Weber. "Trust is tough because it is always

linked to vulnerability, conflict, and ambiguity. For managers steeped

in rationalism, hierarchies, rule-based decision making, and authority

based on titles, this triad of vulnerability, conflict, and ambiguity

threatens a loss of control."

The technologies of relationships will not ease this fear or

pain. They can strengthen and diversify relationships and trust, but not

make them automatic, easy, or instant. At the forefront in the chore to

cultivate trust—as a business imperative—stands the rugged

hurdle of privacy. No other issue summarizes the unique opportunities

and challenges of the network economy as much as privacy does.

Privacy concerns were once exclusively aimed at Big Brother

government, but net residents quickly realized that commercial

entities—the little brothers on the net—were more worrisome.

James Gleick, a technology correspondent for the New York Times

put it this way: "Whatever the Government may know about us, it

seems that the network itself—that ever-growing complex of

connections and computers—will know more. And no matter how much we

bristle at the idea, we nevertheless seem to want services that the

network can provide only if it knows."

An entire book could be written about the fundamental

conversation between what we want to know about others and what we want

others and the net itself to know about us. But I will make only a

single point about privacy in space of an emerging new economy:

Privacy is a type of conversation. Firms should view

privacy not as some inconvenient obsession of customers that must be

snuck around but more as a way to cultivate a genuine relationship.

The standard rejoinder by firms to objections from customers

for more personal information is, "The more you tell us, the better

we can serve you." This is true, but not sufficient. An individual

can’t comfortably divulge unless there is trust.

Take the trust many people feel in a small town. The

interesting thing about a small town is that the old lady who lived

across the street from you knew every move you made. She knew who came

to visit you and what time they left. From your routine she knew where

you went, and why you were late. Two things kept this knowledge from

being offensive: 1) When you were out, she kept an eye on your place,

and 2) you knew everything about her. You knew who came to visit her and

where she went (and while she was gone you kept an eye on her place).

More important, you knew that she knew. You were aware that she kept an

eye on you, and she knew that you watched her. There was a symmetry to

your joint knowledge. There was a type of understanding, of agreement.

She wasn’t going to rifle through your mailbox, and neither would

you peek in hers, but if you had a party and someone passed out on the

porch, you could count on the neighborhood knowing about it the next

day. And vice versa. The watchers are watched.

One of chief chores in the network economy is to restore

the symmetry of knowledge.

For trust to bloom, customers need to know who knows about

them, and the full details of what they know. They have to have

knowledge about the knower equal to what the knower knows about them. I

would be a lot more comfortable with what the credit companies knew

about me if I knew with great accuracy what they knew about me, how they

know it, and who else they told. And I’d be even more at ease if I

derived some compensation for the value they get for knowing about

me.

Personally, I’m happy for anyone to track all my

activities 24 hours a day, as long as I have a full account of where

that information goes and I get paid for it. If I know who the watchers

are, and they establish a relationship with me (in cash, discounts,

useful information, or superior service, or otherwise), then that

symmetry becomes an asset to me and to them.

We see the first inklings of this trust machinery in

protocols such as Truste. Truste was founded in 1995 as a nonprofit

consortium of web sites and privacy advocates to enhance privacy

relationships in the online marketspace. They have developed an

information standard also called Truste. The first stage is a system of

simple badges posted on the front pages of web sites. These seals alert

visitors—before they enter—of the site’s privacy

policies. The badges declare that either:

- We keep no records of anyone’s visit. Or,

- We keep records but only use them ourselves. We know who

you are so that when you return we can show you what’s new, or

tailor content to your desires, or make purchase transactions easier and

simplified. Or,

- We keep records, which we use ourselves, but we also

share knowledge with like-minded firms that you may also like.

Those three broad approaches encompass most transactions; but

there are as many subvariations as there are sites. (To post the badges

or seal, sites must submit to an audit by Truste, which guarantees to

the public that a site does adhere to the policies they post.) But the

seals are only labels. The real work happens behind the scenes by means

of very sophisticated R-tech.

Here is a hypothetical scenario of a visit to a

Truste-approved commerce site a couple of years hence. I visit the Gap

clothing store online. They notify me that they are a level 2 site; they

remember who I am, my clothes size, and what I bought or even inspected

last time I visited—but they don’t sell that data. In exchange

for information about myself, they offer me a 10% discount. Fine with

me! Makes life easier. I visit the site of Raven Maps, the best

topographical maps in the world. They let me know that my visit with

them is on a level 3 basis—they trade my name and interests, but

nothing else, with other travel-related sites, which they conveniently

list. In exchange they will throw in one free map per purchase. Since

the friends of Raven Map look very intriguing, I say yes. I visit

CompUSA. They want to know everything about me, and they will sell

everything about me, level 3. In exchange, they will lease me a

multimedia computer with all the bells and whistles for free. Okay?

Ummm, maybe. Then I visit ABC, the streaming video TV place. They

declare that they keep no records whatsoever. Whatever shows I watch,

only I know. They keep aggregate knowledge, which they use to lure

advertisers, but not specifics. A lot of people are attracted to this

level 1 total nonsurvelliance, despite the heavy dose of commercials,

and keep coming back.

At the end of the month I get a privacy statement, similar in

format to a credit card statement. It lists all the deals and

relationships I have agreed to that month and what I can expect. It says

I agreed to give the Gap particular personal information, but that

information should go no further than them. I gave a pretty detailed

personal profile to Raven and the three companies they gave it to show

up on my statement. Those three have a one-time use of my data. Raven

owes me a map. In the end I gave CompUSA my entire profile. I am owed a

computer. The nine vendors they sold my info to also show up; they have

unlimited use of my profile and CompUSA web site activities. I’ll

get junk mail from those nine for a while—but my new computer will

be able to filter it all out! In addition, I made a deal with the New

York Times which lets them keep my reading activities, but nothing

else, for a free month’s subscription. Also, my statement shows

that American Airlines got my address from ABC, when they claimed level

1. I’ll have to have my privacy bot contact them and sort that

"mistake" out.

Caller ID, unlisted phone numbers, unlisted email address,

individual-free aggregates, personally encrypted medical records,

passport profiles, temporary pseudonym badges, digital signatures,

biometric passwords, and so on. These are all the technologies

we’ll be using to sort out the messy business of creating

relationships and trust in a network economy.

If only we knew precisely what relationships were. Industrial

productivity was easy to measure. One could ascertain a clear numerical

answer. Relationships, on the other hand, are indefinite, fuzzy,

imprecise, complex, innumerate, slippery, multifaceted. Much like the

net itself.

As we create technologies of relationships we keep running

into the soft notions of reputation, privacy, loyalty, and trust. Unlike

bit or baud, there’s no good definition of what these concepts mean

exactly, though we have some general ideas. Yet we are busy engineering

a network world to transmit and amplify reputations and loyalty and

trust. The hottest, hippest frontiers on the net today are the places

where these technologies are being developed.

The network economy is founded on technology, but can

only be built on relationships. It starts with chips and ends with

trust.

Ultimately the worth of a technology is judged by how well it

facilitates an increase in relational activity. VR pioneer Jaron Lanier

has proposed the Connection Test: Does a technology in question connect

people together? By his evaluation telephones are good technology, while

TV is not. Birth control pills are, while nuclear power is not.

By this measure, network technology is a great deal. It has

the potential to link together all kinds of sentient beings in every

imaginable way, and more. The imperative of the network economy is to

maximize the unique talents of individual beings by means of their

relationships with many others.

That means not being connected at times. Silence is often an

appropriate response in a conversation. Privacy is often advantageous in

a networked world. The dimensions of relationship extend into not

knowing as well as into the known. It is one of many mysteries in the

human condition that will be wired into the technologies of the network

economy.

Strategies

Make customers as smart as you are. For every effort a

firm makes in educating itself about the customer, it should expend an

equal effort in educating the customer. It’s a tough job being a

consumer these days. Any help will be rewarded by loyalty. If you

don’t educate your customer, someone else will—most likely

someone not even a competitor. Almost any technology that is used to

market to customers, such as data mining, or one-to-one techniques, can

be flipped around to provide intelligence to the customer. No one is

eager for a core dump, but if you can remember my trouser size, or

suggest a movie that all my friends loved, or sort out my insurance

needs, then you are making me smarter. The rule is simple: Whoever has

the smartest customers wins.

Connect customers to customers. Nothing is as scary to

many corporations as the idea of sponsoring dens in which customers can

talk to one another. Especially if it is an effective place of

communication. Like the web. "You mean," they ask in wonder,

"we should pay a million dollars to develop a web site where

customers can swap rumors and make a lot of noise? Where complaints will

get passed around and the flames of discontent fanned?" Yes,

that’s right. Often that’s what will happen. "Why should

we pay our customers to harass us," they ask, "when they will

do that on their own?" Because there is no more powerful force in

the network economy than a league of connected customers. They will

teach you faster than you could learn any other way. They will be your

smartest customers, and, to repeat, whoever has the smartest customers

wins.

Just recently E-trade, the pioneering online stock broker,

took the bold step of setting up an online chat area for its customers.

We’ll see more smart companies do this. Whatever tools you develop

that will aid the creation of relationships between your customers will

strengthen the relationship of your customers to you. This effort can

also be thought of as Feeding the Web First.

All things being equal, choose technology that

connects. Technology tradeoffs are made daily. A device or method

cannot be the fastest, cheapest, more reliable, most universal, and

smallest all at once. To excel, a tech has to favor some dimensions over

others. Now add to that list, most connected. This aspect of technology

has increasing importance, at times overshadowing such standbys as speed

and price. If you are in doubt about what technology to purchase, get

the stuff that will connect the most widely, the most often, and in the

most ways. Avoid anything that resembles an island, no matter how well

endowed that island is.

Imagine your customers as employees. It is not a cheap

trick to get the customer to do what employees used to do. It’s a

way to make a better world! I believe that everyone would make their own

automobile if it was easy and painless. It’s not. But customers at

least want to be involved at some level in the creation of what they

use—particularly complex things they use often. They can

superficially be involved by visiting a factory and watching their car

being made. Or they can conveniently order a customized list of options.

Or, through network technology, they can be brought into the process at

various points. Perhaps they send the car through the line, much as one

follows a package through FedEx. Smart companies have finally figured

out that the most accurate way to get customer information, such as a

simple address, without error, is to have the customer type it

themselves right from the first. The trick will be finding where the

limits of involvement are. Customers are a lot harder to get rid of than

employees! Managing intimate customers requires more grace and skill

than managing staff. But these extended relationships are more powerful

as well.

The final destiny for the future of the company often seems

to be the "virtual corporation"—the corporation as a

small nexus with essential functions outsourced to subcontractors. But

there is an alternative vision of an ultimate destination—the

company that is only staffed by customers. No firm will ever reach that

extreme, but the trajectory that leads in that direction is the right

one, and any step taken to shift the balance toward relying on the

relationships with customers will prove to be an advantage.

continue...

|